"Purchase 80mg diovan fast delivery, blood pressure cuff cvs".

N. Zakosh, M.A., Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Ponce School of Medicine

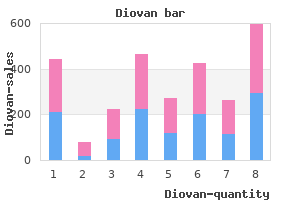

Notes: Data for conventional cigarettes are from 32 tobacco cigarette smokers using their usual brand of cigarette (Vansickel et al. Ecigarette A is a cigalike called "blu" loaded with two different concentrations of liquid nicotine (16 or 24 mg/mL, both containing 20% propylene glycol and 50% vegetable glycerin). Youth and Young Adults 103 A Report of the Surgeon General (Continued from last paragraph on page 102. Regardless, among 766 adults, who were daily users of ecigarettes (with nicotine) and who were either former cigarette smokers (83%) or current cigarette smokers (17%), 30. However, it is important to note that ecigarettes were less addictive than conventional cigarettes in this sample (Etter and Eissenberg 2015). More generally, the delivery of nicotine in sufficient doses and blood concentration would be expected to produce and maintain dependence in ecigarette users. Further work would be useful to determine the natural course and history of ecigarette use among smokers of conven tional cigarettes, former smokers, and never smokers and to more accurately determine the nicotine addiction lia bility of ecigarette use. Unfortunately, these issues have not been explored in adolescents, although the prevalence of ecigarette use has increased considerably in that popu lation since 2011 (see Chapter 2). Effects of Nicotine in Youth Users Nicotine is the prime psychoactive substance in con ventional cigarettes (Yuan et al. Although much of the literature on nicotine addiction arises from studies of nicotine exposure among adults, and with combus tible tobacco products (see Table A3. These animal and human studies, taken together with studies of rising ecigarette prevalence in youth (see Chapter 2), point to an agedependent suscep tibility to nicotine as a neurobiological insult. Limited direct human experimental data exist on the effects of nicotine exposure from ecigarettes on the developing adolescent brain, but experimental laboratory data have been found to be relevant in animal models to contextualize effects in humans (Stevens and Vaccarino 2015). Even if the full complexity of human brain develop ment and behavioral function during adolescence cannot be completely modeled in other species, the similarities across adolescents of different species support the use of animal models of adolescence when examining neural and environmental contributors to adolescentcharacteristic functioning (Spear 2010). Animal studies provide an effective method to examine the persistent effects of prenatal, child, and ado lescent nicotine exposure, in addition to human epide miologic data. When considering an epidemiologic causal argument of exposure (risk factor) to health outcome (dis ease), one should note that animal models lend biolog ical plausibility when experimentation with humans is not possible (or ethical) (Rothman et al. Furthermore, animal studies offer significant advantages compared to human studies-with the ability to control for many con founding factors, to limit nicotine exposure to differing levels of physical and neural development-and are piv otal for understanding the neural substrates associated with adolescence. The validity of any causal argument when examining animal models requires careful consider ation, and yet in combination with epidemiologic data- such as prevalence, incidence, and strength of association between exposure and outcome-a causal argument can be constructed with literature from animal models rep resenting biologic plausibility. Using a variety of study designs and research paradigms including humans and animals, research in this area provides evidence for neu roteratogenic and neurotoxic effects on the developing adolescent brain (Lydon et al. The brain undergoes significant neurobiological development during adolescence and young adulthood, which are critical periods of sensitivity to neurobiolog ical insults (such as nicotine) and experienceinduced plasticity (Spear 2000; Dahl 2004; Gulley and Juraska 2013). Although maturation occurs in different regions of the brain at different rates, a similar progression occurs in all areas characterized by a rapid formation of syn aptic connections in early childhood, followed by a loss of redundant or unnecessary synapses (called pruning) and the formation of myelin. Myelination is the process by which a fatty layer, called myelin, accumulates around 104 Chapter 3 E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults nerve cells (neurons). Because of myelin, nerve cells can transmit information faster, allowing for more complex brain processes. Pruning allows for more focused con centration, and myelination allows for faster electrical and neural signaling; both allow for more efficient cog nitive processing. During adolescence and into young adulthood, myelination occurs rapidly in the frontal lobe, a place in the brain that controls executive functioning, reasoning, decisionmaking skills, selfdiscipline, and impulse control. Plasticity refers to the current under standing that the brain continues to change throughout life, not only because of normal, maturational neural growth and development but also because of changes in environmental neurobiological exposures (such as nico tine), injuries, behaviors, thinking, and emotions (Mills and Tamnes 2014). Across species, and in humans, adolescence is a key period of increased plasticity and rapid growth of brain circuits that regulate social, emotional, and motivational processes and decision making (Spear 2000, 2011; Nelson et al. The prefrontal cortex, which is involved in higher level regulatory control of complex behaviors (such as plan ning, impulse control, and working memory), continues normal structural and functional development into young adulthood, to about 25 years of age (Giedd and Rapoport 2010; Somerville and Casey 2010). Because of the immatu rity and rapid growth of the prefrontal cortex, adolescents and young adults normally exhibit moody, risktaking, and unpredictable impulsive behaviors. The combina tion of delayed maturation of frontal cognitive control and increased reactivity of subcortical rewardrelated and emotionprocessing systems may lead to increased risktaking behavior and a greater susceptibility to initi ating substance use and the development of dependence (Steinberg 2008; Ernst and Fudge 2009; Counotte et al.

Affected individuals may appear alert but dazed and unre sponsive, consistent with catatonic stupor. Autonomic activation and instability-mani fested by tachycardia (rate >25% above baseline), diaphoresis, blood pressure elevation (systolic or diastolic >25% above baseline) or fluctuation (>20 mmHg diastolic change or >25 mmHg systolic change within 24 hours), urinary incontinence, and pallor-may be seen at any time but provide an early clue to the diagnosis. Tachypnea (rate >50% above baseline) is common, and respiratory distress-resulting from metabolic acidosis, hyper metabolism, chest wall restriction, aspiration pneumonia, or pulmonary emboli-can oc cur and lead to sudden respiratory arrest. A workup, including laboratory investigation, to exclude other infectious, toxic, met abolic, and neuropsychiatric etiologies or complications is essential (see the section "Dif ferential Diagnosis" later in this discussion). Although several laboratory abnormalities are associated with neuroleptic malignant syndrome, no single abnormality is specific to the diagnosis. Individuals with neuroleptic malignant syndrome may have leukocytosis, metabolic acidosis, hypoxia, decreased serum iron concentrations, and elevations in se rum muscle enzymes and catecholamines. Findings from cerebrospinal fluid analysis and neuroimaging studies are generally normal, whereas electroencephalography shows gen eralized slowing. Autopsy findings in fatal cases have been nonspecific and variable, de pending on complications. Development and Course Evidence from database studies suggests incidence rates for neuroleptic malignant syn drome of 0. The temporal pro gression of signs and symptoms provides important clues to the diagnosis and prognosis of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Alteration in mental status and other neurological signs typically precede systemic signs. Some cases develop within 24 hours after drug initiation, most within the first week, and virtually all cases within 30 days. Once the syndrome is diagnosed and oral antipsychotic drugs are discontinued, neuroleptic malignant syndrome is self-limited in most cases. The mean recovery time after drug discontinuation is 7-10 days, with most individuals recovering within 1 week and nearly all within 30 days. There have been reports of in dividuals in whom residual neurological signs persisted for weeks after the acute hypermetabolic symptoms resolved. Total resolution of symptoms can be obtained in most cases of neuroleptic malignant syndrome; however, fatality rates of 10% -20% have been reported when the disorder is not recognized. Although many individuals do not experi ence a recurrence of neuroleptic malignant syndrome when rechallenged with antipsy chotic medication, some do, especially when antipsychotics are reinstituted soon after an episode. Risk and Prognostic Factors Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is a potential risk in any individual after antipsychotic drug administration. It is not specific to any neuropsychiatric diagnosis and may occur in individuals without a diagnosable mental disorder who receive dopamine antagonists. Clinical, systemic, and metabolic factors associated with a heightened risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome include agitation, exhaustion, dehydration, and iron deficiency. A prior episode associated with antipsychotics has been described in 15%-20% of index cases, suggesting underlying vulnerability in some patients; however, genetic findings based on neurotransmitter receptor polymorphisms have not been replicated consistently. Nearly all dopamine antagonists have been associated with neuroleptic malignant sjmdrome, although high-potency antipsychotics pose a greater risk compared with lowpotency agents and newer atypical antipsychotics. Partial or milder forms may be associ ated with newer antipsychotics, but neuroleptic malignant syndrome varies in severity even with older drugs. Parenteral administration routes, rapid titration rates, and higher total drug dosages have been associated with increased risk; however, neuroleptic malignant syndrome usually occurs within the therapeutic dos age range of antipsychotics. Differential Diagnosis Neuroleptic malignant syndrome must be distinguished from other serious neurological or medical conditions, including central nervous system infections, inflammatory or au toimmune conditions, status epilepticus, subcortical structural lesions, and systemic con ditions. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome also must be distinguished from similar syndromes resulting from the use of other substances or medications, such as serotonin syndrome; parkinsonian hyperthermia syndrome following abrupt discontinuation of dopamine ag onists; alcohol or sedative withdrawal; malignant hyperthermia occurring during anes thesia; hyperthermia associated with abuse of stimulants and hallucinogens; and atropine poisoning from anticholinergics. In rare instances, individuals with schizophrenia or a mood disorder may present with malignant catatonia, which may be indistinguishable from neuroleptic malignant syn drome. Some investigators consider neuroleptic malignant syndrome to be a druginduced form of malignant catatonia. In some patients, movements of this type may appear after discontinuation, or after change or reduction in dosage, of neuroleptic medications, in which case the condition is called neuroleptic withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia. Because withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia is usually time-limited, lasting less than 4-8 weeks, dyskinesia that persists beyond this win dow is considered to be tardive dyskinesia.

Iatrogenic effects of psychosocial interventions: treatment, life context, and personal risk factors. Mother-infant interaction: effects of a home intervention and ongoing maternal drug use. Identifying patients "at risk" for alcohol withdrawal syndrome and a treatment protocol. A reinforcement-based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: six-month abstinence outcomes. Psychological and/or educational interventions for reducing alcohol consumption in pregnant women and women planning pregnancy. Psychosocial interventions for pregnant women in outpatient illicit drug treatment programs compared to other interventions. Psychosocial interventions include a number of psychological treatments and social supports, ranging from lesser to higher intensity. The psychosocial treatment and support referred to in this section is a more intensive set of interventions typically delivered by people with specific training in the management of substance use disorders, and usually includes repeated contact with the patient. The kinds of specific psychological techniques considered in this category include cognitive behavioural therapy, contingency management and motivational enhancement. The kinds of social support referred to in this section include assistance with accommodation, vocational training, parenting training, life-skills training, legal advice, home visiting and outreach. Research recommendations o Better reporting and agreement on standardized designs and outcomes is needed. Intensified Case Management: As for Routine Case Management, but women also received bi-weekly case management services by telephone or in person (on-site at the treatment facility or through home visits). Intensive case management services focused on assessment, planning for necessary services and interventions, establishment of linkages with relevant agencies, monitoring of patient follow through with scheduled appointments and advocacy for the patient when needed to successfully navigate the health-care system. Routine Case Management: Offered at scheduled paediatric visit at clinic of treatment service: 2 wks, 1, 2 and 4 months postpartum. Women were asked about their status in substance abuse treatment, needs for themselves and their infants, and compliance with treatment, paediatric care, maternal health, and postpartum care and family planning. Settings: Specialist treatment outpatient Bibliography: Psychosocial interventions for pregnant or postpartum women with problematic substance use. Randomization did not result in similar numbers in each group indicating a possible effect of chance or selection bias. Guidelines for the identification and management of substance use and substance use disorders in pregnancy 55 Guidelines for the identification and management of substance use and substance use disorders in pregnancy 56 Alcohol and drug use Setting (duration) Study duration Randomized groups Primary outcomes On Methadone programme & the selfreported injection of any drug within the previous 6 months Outpatient. Two hospital-based reproductive health clinics with appointments coordinated with regular prenatal visits. Content included motivational enhancement, functional analysis, safe sexual behavior, communication skills, relapse prevention and problem-solving skills. Delivered by a nurse therapist who had flexibility to offer additional treatment sessions according to time and need. Each session lasted approximately 30 min Brief advice: Brief advice covered risks of substance use, the importance of abstinence, and the benefit of seeking drug and alcohol treatment outside of the prenatal setting. A likely lack of blinding for providers and participants in both trials may have introduced performance bias. In Yonkers 2012 the proxy measure is attending at least one of 6 session during the entire study period which continued to 3 months postpartum. Settings: General treatment settings (antenatal) and specialist substance use programmes: Outpatient Bibliography: Psychosocial interventions for pregnant or postpartum women with problematic substance use. The measurement for treatment retention used in the analysis is a proxy measure for both trials. The mean duration of follow-up was calculated as from 28 weeks to delivery although women may have been in treatment for longer if enrolled before 28 weeks. This well-conducted trial Yonkers 2012 was down-graded on the basis of a likely lack of blinding which may have introduced performance bias. Results of other trials from which data could not be extracted are included in the footnotes.

With poor insight: the individual thinks that the body dysmorphic disorder beliefs are probably true. With absent insight/delusionai beliefs: the individual is completely convinced that the body dysmorphic disorder beliefs are true. Diagnostic Features Individuals with body dysmorphic disorder (formerly known as dysmorphophobia) are pre occupied with one or more perceived defects or flaws in their physical appearance, which they believe look ugly, unattractive, abnormal, or deformed (Criterion A). The perceived flaws are not observable or appear only slight to other individuals. Concerns range from looking "unattractive" or "not right" to looking "hideous" or "like a monster. The preoccupations are intrusive, unwanted, time-consuming (occurring, on average, 3-8 hours per day), and usually difficult to resist or control. The individual feels driven to perform these be haviors, which are not pleasurable and may increase anxiety and dysphoria. Compulsive skin picking intended to improve perceived skin defects is common and can cause skin damage, infections, or ruptured blood vessels. The preoccupation must cause clinically significant distress or im pairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning (Criterion C); usually both are present. Individuals with this form of the disorder actually have a nor mal-looking body or are even very muscular. A majority (but not all) diet, exercise, and/or lift weights excessively, sometimes causing bodily damage. Some use potentially dangerous anabolic- androgenic steroids and other substances to try to make their body bigger and more mus cular. Insight regarding body dysmorphic disorder beliefs can range from good to absent/ delusional. On average, insight is poor; onethird or more of individuals currently have delusional body dysmorphic disorder beliefs. Individuals with delusional body dysmorphic disorder tend to have greater morbidity in some areas. Associated Features Supporting Diagnosis Many individuals with body dysmorphic disorder have ideas or delusions of reference, believing that other people take special notice of them or mock them because of how they look. Body dysmorphic disorder is associated with high levels of anxiety, social anxiety, social avoidance, depressed mood, neuroticism, and perfectionism as well as low extro version and low self-esteem. Many individuals are ashamed of their appearance and their excessive focus on how they look, and are reluctant to reveal their concerns to others. A majority of individuals receive cosmetic treatment to try to improve their perceived de fects. Body dysmorphic disorder appears to respond poorly to such treatments and sometimes becomes worse. Some individuals take legal action or are violent toward the clinician because they are dissatisfied with the cosmetic outcome. Body dysmorphic disorder has been associated with executive dysfunction and visual processing abnormalities, with a bias for analyzing and encoding details rather than ho listic or configurai aspects of visual stimuli. Individuals with this disorder tend to have a bias for negative and threatening interpretations of facial expressions and ambiguous sce narios. Deveiopment and Course the mean age at disorder onset is 16-17 years, the median age at onset is 15 years, and the most common age at onset is 12-13 years. Subclinical body dysmorphic disorder symptoms begin, on average, at age 12 or 13 years. Subclinical concerns usually evolve gradually to the full disorder, although some individuals experience abrupt onset of body dysmorphic disorder. The disorder appears to usually be chronic, although improvement is likely when evidence-based treatment is received. Body dysmohic disorder occurs in the elderly, but little is known about the disorder in this age group. Individuals with disorder onset before age 18 years are more likely to attempt suicide, have more comorbidity, and have gradual (rather than acute) disorder onset than those with adult-onset body dysmorphic disorder.

A pilot study of the effects of high-intensity aerobic exercise versus passive interventions on pain, disability, psychological strain, and serum cortisol concentrations in people with chronic low back pain. The efficacy of an aerobic exercise and health education program for treatment of chronic low back pain. Functional restoration versus outpatient physical training in chronic low back pain: a randomized comparative study. Outcome evaluation of work hardening program for manual workers with work-related back injury. Return-towork status 1 year after muscle reconditioning in chronic low back pain patients. Efficacy of a functional restoration program for chronic low back pain: Prospective 1-year study. A multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme for patients with chronic low back pain: a prospective study. Comparison of a functional restoration program with active individual physical therapy for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Intensive group training protocol versus guideline physiotherapy for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. A therapist performed spinal manipulation on all patients during an initial session. Participants reported disability and attended a second treatment session 2-4 days after the initial session. If disability improvement was >50%, the study participant was ended due to success in treatment. If disability improvement was<50%, the participant attended one final treatment session after 2-4 days. Patients were also instructed to complete pelvic tilt range of motion exercise and maintain usual activity levels within pain limits. Statistical analyses aimed to determine the association between individual variables from the initial examination and categorization of successful treatment. Patients who received manipulation had greater improvements in disability and pain than those who received exercise alone. The patients who were positive on the rule and received manipulation had greater improvement in disability and pain at all follow-up points compared to patients who were negative on the rule and received manipulation. Active exercise therapy included directional preference exercises, lumbar stabilization, general flexibility and specific training exercises. The participants in the intervention group (n=120) received sham ultrasound for the same duration of time. Pain (11-point scale) and disability (24-point Roland Morris disability questionnaire) were recorded at 1, 2, 4 and 12 weeks. There were no significant interaction effects in pain or disability between treatment groups and prediction rule classification. The intervention group (n=31) received 4 sessions of manipulative therapy along with physical therapy (low intensity endurance exercises). The patients who received manipulation therapy had a greater improvement in disability compared to the control group, but there were no significant differences in pain or mobility. The authors concluded that although there were statistically significant interaction effects for disability and sex, these had low effect size and there were no significant effects for pain or mobility. This study provides Level I prognostic evidence that the addition of manipulative therapy added benefit over physical therapy alone for improving disability. Diagnosis & Treatment of Low Back Pain Recommendations Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation There is insufficient evidence that hyper- or hypo-mobility, patient age, strains and sprains, instability, severe affective distress, relationship with healthcare provider, use of thrust vs. All participants received manual therapy for 2 visits, either thrust (n=76) or non-thrust (n=73). Logistic and linear regression modeling were used to create predictive models and find significant explanatory power for the outcome variables. Participants were classified as nonresponders to therapy if their changes in Roland Morris Disability score improved by less than <2. Potential predictors of response, including demographics, baseline disability and pain intensity and life satisfaction, were analyzed using multivariable backward logistic regression to predict the probability of nonresponse to treatment. The authors concluded that a lower baseline Roland Morris Disability score predicted nonresponse for physiotherapy, but not for spinal manipulation. Participants (n=100) had been randomized to receive thrust or nonthrust manipulation, along with a home exercise program.