"Order cardura online now, blood pressure medication icu".

A. Vak, M.A., M.D., M.P.H.

Medical Instructor, University of Connecticut School of Medicine

A group of organisms that lack chlorophyll, induding molds, mildews, yeasts, mushrooms. A pest management strategy that focuses on long-tear prevention or suppression of pest problems through a combination of techniques such as monitoring for pest presence and establishing treatment threshold levels, using non-chemical practices to make the habitat less conducive to pest development, improving sanitation, and employing mechanical and physical controls. Pesticides that pose the~least possible hazard and are effective in a manner that minimizes risks to people, property, and the environment, are used only after careful monitoring indicates they are needed according to preestablished guidelines and treatment thresholds. The movement of outdoor air into a space through intentionally provided openings, such as windows and doors, or through nonmechanical ventilators, by wind, air pressure differences, or other natural, non-mechanical means. A pesticide is any substance or mixture of substances intended to prevent, destroy, repel, or mitigate any pest. Though often misunderstood to refer only to insecticides, the term pesticide also applies to herbicides, fungicides, disinfectants, and antimicrobials. They are a common product of combustion from automobiles, airplanes, woodburning, cigarettes, and some types of cooking. Classrooms that are designedand constructed to be moveable and transportable over public streets, also known as temporary or relocatable dassrooms. Methods for determining the operation include blanks, spiked samples, flow checks, and duplicate samples. This type of environmental measurement gives instantaneous information at the point of sampling: measurements are recorded as often as every minute, every second, or in fractions of a second. The concentration level at or below which~no adverse health effects are anticipated for a specified exposure duration. The measure of moisture in the atmosphere, expressed as a percent of the maximum moisture the air can hold at a given temperature. A set of symptoms (including headache, fatigue, and eye irritation) typically affecting workers in modem airtight oftice buildings, believed to be caused by indoor pollutants (such as formaldehyde fumes or microorganisms). Air handling system that conditions the air to a temperature using a varying amount of outside aifflow based essentially on the outdoor temperature. The process of intentionally supplying and removing air by natural or mechanical means to and from any space. Compounds that evaporate quickly from the many housekeeping, maintenance, and building products made with organic chemicals. These compounds are released from products that are being used and that are in storage. The state board shall develop these options in consultation with representatives from school district facility departments, school district maintenance departments, and statewide educational organizations. If the state board disagrees with any aspect of the findings of the external scientific peer review. This information is the best information available for California, and the indoor air concentrations on which these estimates are based are supported by more recent studies from other states. In the C&P Project, the outdoor contribution to the indoor concentrations was subtracted from the indoor levels, with the remainder attributable to indoor sources. This is somewhat different from the expression we typically use for outdoor air, expressed as cancer risk from 70 years of exposure per million people exposed, but the two can be roughly converted for comparison (see below). The risk from residential and consumer products was ranked in the High Risk category with a high level of confidence based on the extensive contribution to both cancer and non-cancer risks, the widespread exposure throughout the population, and the consistency of monitoring results across many studies. They are based on exposure distributions developed from the best available studies at the time, with greater weight given to California studies. Generally, 34 California studies of large numbers of homes in both northern and southern California (totaling about 606 800 homes) were available; these covered a range of seasons, income levels, etc. Indoor concentrations tend to be log-normally distributed, meaning a small but decreasing portion of the population experiences particularly high exposures well above the mean. Because of this, wncentration distributions (rather than means) were used to develop exposure estimates to achieve more accurate risk estimates. Although distributions were used to estimate risk, the resulting average individual risk was used to estimate annual cancer cases, and thus these may be conservative estimates, since the average does not necessarily fully capture those at very high risk. Additionally, only the population with an exposure level above the one in ten thousand risk level was included in the risk estimation; thus, those with lower cancer risks were not counted, effectively reducing the total count relative to the population estimate that would be derived if those with lower cancer risks had also been included. Formaldehyde is the only one of the 10 indicator chemicals for which there are sufficient new data to develop a more current exposure distribution.

For example, ozone forms differently in the Houston region than in the Dallas-Fort Worth region. Industry investments in cutting-edge control technology and in enhanced operational management were key to the Texas success. Air Quality Research Texas has invested more money in air quality research over the last 10 years than any state In the country. These reforms will not rollback existing, effective protection of air quality but will foster more rapid, costefficient management of genuine air quality challenges. Congress should reclaim its constitutional authority to make the fundamental policy decisions about air quality; such as determination of the National Ambient Air Quality Standards and approval of major regulations. It must, further, relegate science to its proper role as a critical tool to guide policy decisions about environmental risk but not as a means of dictating policy decisions. Those regions with interstate air quality problems can address them regionally through interstate compacts or other legal mechanisms. Most critically, federal policies about air quality need to incorporate fundamental principles of individual liberty, private property, and the free market. The air quality improvements over the last 40 years were driven by innovation, efficiency, and economic growth. Economic freedom has powerful environmental benefits, because liberty promotes objectivity, creativity, investment, and problem-solving. This law no longer provides an effective, scientifically credible or economically viable means of air quality management. In our constitutional scheme, the courts are supposed to keep agency actions within the bounds of the law passed by Congress. The condition or trend of air quality is measured in terms of ambient levels in the air and emission volumes. The ambient levels are the key measure of health impacts because they are a physical measurement of the actual concentrations of pollutants in the air to which humans are exposed. Emissions are an estimate of the volume of pollutants released to the air by human activities. Ambient levels are physically measured by monitors across the country, while emissions are estimated by models. Emissions of lead have declined by 97 percent, largely a result of eliminating lead in transportation fuels. Market~driven operational efficiencies, to avoid costly wastes, simultaneously reduced emissions and conserved energy use. Privately-owned enterprises, acting in a free market under a predictable and limited government, prospered and were thus able to absorb the steep costs of environmental controls. As the Environmental Performance Index, 10 the Heritage Foundation Index of Economic Freedom, the Fraser Institute, and other studies 11 consistently demonstrate, those countries which structurally enshrine economic liberty under the rule of clear and limited laws also achieve environmental success. Environmental quality remains an unatfordable luxury for most of the developing world and an elusive goal for countries that deny or undermine property rights. Objective science, innovative technology, entrepreneurial investments of capital and rapid information exchange: these hallmark,<; of the free market maximize continual environmental enhancements. Rising food and energy prices, coupled,vi,th high unemM ployment, have pushed poverty rates to the highest levels in 52 years. Morbidity (illness) and shortened lifespan (premature mortality) are far more directly correlated with poverty and unemployment than with air quality, 12 A Comparison of Crime Rate, Welfare, and Air Pollution, 1970-2007 60. Require annual advisory reports that contain cumulative regulatory impact analyses of risk, cost, effectiveness and benefits based on a methodology and scope determined by Congress and conducted by a third party. Restore Congressional Authority and Accountability As articulated in federal law, the definition ofhealthy air is a matter of policy for the elected branches of government. These involve a complex balancing of interests, risks, costs, diverse benefits, relative effectiveness, and inherent scientific uncertainties. Congress not only created the programs but specified the extent of emission reductions, the timetable, and the parties expected to bear the burdens.

Rising Up Off the Page Just as our solution is ours, their solution has to be theirs. What is called "animal law" has been human law: the laws of humans on or for or about animals. Otani was unconscious when injured and died several hours later without regaining consciousness. In the wrongful death action, the trial court awarded damages of $125,000 each to Ms. In the survival action, the court awarded the estate $450,000 for "Loss of enjoyment of life which includes shortened life expectancy," as well as $3,854 for burial expenses and $42,762. Loss of enjoyment of life must likewise be experienced in life before it can become the basis for an award of damages. For this reason, it is available in a personal injury action, but not in a survival action. Kyle, "people have been trying to understand dogs ever since the beginning of time. You can read every day where a dog saved the life of a drowning child, or lay down his life for his master. We conclude it is not, and reverse an award of $450,000 to the estate of a decedent who died shortly after surgery without conscious pain or awareness that she had been fatally injured. Had the decedent lived, she would have had no claim for loss of life; therefore, no such claim survived to her personal representative. Otani in the few short hours between her injury and her death, and thus we are not asked to decide whether such damages would be available in the case of a person who was comatose for an extended period before death. Rather, the question is whether to award damages for a number of years after death. Pecuniary damages, on the other hand, compensate the victim for the economic consequences of the injury, such as medical expenses, lost earnings, and the cost of custodial care. The specific questions raised here deal with assessment of nonpecuniary damages and are (1) whether some degree of cognitive awareness is a prerequisite to recovery for loss of enjoyment of life and (2) whether a jury should be instructed to consider and award damages for loss of enjoyment of life separately from damages for pain and suffering. We answer the first question in the affirmative and the second question in the negative. On September 7, 1978, plaintiff Emma McDougald, then 31 years old, underwent a Caesarean section and tubal ligation at New York Infirmary. Defendant Garber performed the surgery; defendants Armengol and Kulkarni provided anesthesia. McDougald suffered oxygen deprivation which resulted in severe brain damage and left her in a permanent comatose condition. A jury found all defendants liable and awarded Emma McDougald a total of $9,650,102 in damages, including $1,000,000 for conscious pain and suffering and a separate award of $3,500,000 for loss of the pleasures and pursuits of life. The balance of the damages awarded to her were for pecuniary damages-lost earnings and the cost of custodial and nursing care. Garber Court of Appeals of New York (1989) this appeal raises fundamental questions about the nature and role of nonpecuniary damages in personal injury litigation. On cross appeals, the Appellate Division affirmed and later granted defendants leave to appeal to this court. McDougald responded to certain stimuli to a sufficient extent to indicate that she was aware of her circumstances. The goal is to restore the injured party, to the extent possible, to the position that would have been occupied had the wrong not occurred. To be sure, placing the burden of compensation on the negligent party also serves as a deterrent, but purely punitive damages-that is, those which have no compensatory purpose-are prohibited unless the harmful conduct is intentional, malicious, outrageous, or otherwise aggravated beyond mere negligence. Damages for nonpecuniary losses are, of course, among those that can be awarded as compensation to the victim. This aspect of damages, however, stands on less certain ground than does an award for pecuniary damages. We have no hope of evaluating what has been lost, but a monetary award may provide a measure of solace for the condition created. Our willingness to indulge this fiction comes to an end, however, when it ceases to serve the compensatory goals of tort recovery. When that limit is met, further indulgence can only result in assessing damages that are punitive.

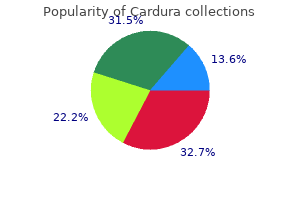

For instance, average market income per person in the lowest-income quintile of the population (the bottom 20 percent based on household income) is an average of $4,800 before taxes and transfers. In contrast, among the highest-income quintile the average income per person is $105,000. But market income presents only a partial view of the material well-being of American households. Once households are ranked by size-adjusted income, each quintile is set to include the same number of individuals. We measure per person income as the aggregate household income of each income group divided by the number of people in that group. The red bars show average income per person after social insurance, transfers, and federal taxes. The after-tax, after-transfer income of individuals in the lowest-income households is lifted to $15,200-hence, federal tax and transfer programs triple the incomes of low-income, non-elderly individuals relative to what they earn in the market alone. For households in the top income quintile, transfers and federal taxes reduce market incomes from an average of $105,000 per person to $77,000-or 27 percent less. This effect is more pronounced for higher incomes, with top 1 percent incomes reduced by 34 percent. In other words, the net effect of taxes and transfers is to reduce disparities that exist when considering only market income. While these redistributive effects are clearest among the lowest-income and highest-income households because of the progressive tax and transfer system, it is also apparent among middle-class households. While there is not a formal definition of who is middle class, we focus on the middle three quintiles of the population. Figure 1 shows that, on average, public policies modestly boost the incomes of non-elderly households in the second quintile (lower-middle class households) and slightly reduce the incomes of upper-middle class households. It is not just the bottom of the income distribution that benefits from the progressive tax and transfer system. An additional consideration is that a significant share of federal tax revenue is not redistributed to households as means-tested transfers or social insurance, but instead finances federal purchases such as education, roads, defense, and other public goods that yield value to most households. While the value of such public goods is not included in our analysis, the taxes that finance them are. Including the benefits from these public goods would raise the well-being of low- and middleincome households above that measured by disposable income alone. These excluded sources total more than $1 trillion in 2014 (Auten and Splinter 2019b). However, we do not attempt to adjust the income definitions and distributional estimates from their data. Each of these are important sources of middle-class income and accounting for them would boost the level of middle-class income and its growth (Auten and Splinter 2019a; Sabelhaus and Volz 2020). In this section, we discuss the growth in total transfers and the recent distribution of transfers and federal taxes. We also discuss how tax expenditures and social insurance benefits benefit the middle class, often protecting them from economic insecurity, and why standard approaches may understate the degree to which they accrue to the middle class. Transfers Are a Growing Share of Federal Spending Transfer programs reflect a sizeable share of federal expenditures. In 2019, 23 percent of federal spending paid for Social Security and 15 percent provided insurance through Medicare. Hence, these two social insurance programs reflected 38 percent of all federal spending. As noted above, standard measures of after-tax, after-transfer income exclude the value of non-transfer spending, which represents a bit less than half of federal spending. Over time, the amount that the federal government spent on social insurance, transfers, and other investments in material well-being increased both as a share of the federal budget and as a share of the economy. This increase was accommodated largely with reductions in defense spending-a peace dividend-but also lower interest costs and a higher budget deficit. In other words, in 1979 roughly half of government spending was devoted to social insurance, means-tested transfers, or investments in the health, education, and economic security of Americans. On net, the federal government now devotes more resources to improve the material well-being of Americans than ever before. But the size of transfer programs has increased in recent decades even excluding elderly households.