"Buy cialis professional australia, erectile dysfunction diabetes medication".

O. Hamlar, MD

Clinical Director, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

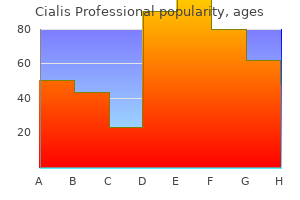

During later phases of an ongoing pandemic, testing may be necessary for many more patients, so that appropriate treatment and infection control decisions can be made, and to assist in defining the extent of the pandemic. Patients with confirmed or suspected H5N1 influenza should be treated with oseltamivir. Most H5N1 isolates since 2004 have been susceptible to the neuraminidase inhibitors oseltamivir and zanamivir and resistant to the adamantanes (amantidine and rimantidine) [262, 263]. The current recommendation is for a 5-day course of treatment at the standard dosage of 75 mg 2 times daily. In addition, droplet precautions should be used for patients with suspected H5N1 influenza, and they should be placed in respiratory isolation until that etiology is ruled out. Health care personnel should wear N-95 (or higher) respirators during medical procedures that have a high likelihood of generating infectious respiratory aerosols. Bacterial superinfections, particularly pneumonia, are important complications of influenza pneumonia. Legionella, Chlamydophila, and Mycoplasma species are not important causes of secondary bacterial pneumonia after influenza. Appropriate agents would therefore include cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, and respiratory fluoroquinolones. Because shortages of antibacterials and antivirals are anticipated during a pandemic, the appropriate use of diagnostic tests will be even more important to help target antibacterial therapy whenever possible, especially for patients admitted to the hospital. This emphasis is based on 2 retrospective studies of Medicare beneficiaries that demonstrated statistically significantly lower mortality among patients who received early antibiotic therapy [109, 264]. The initial study suggested a breakpoint of 8 h [264], whereas the subsequent analysis found that 4 h was associated with lower mortality [109]. Studies that document the time to first antibiotic dose do not consistently demonstrate this difference, although none had as large a patient population. For these and other reasons, the committee did not feel that a specific time window for delivery of the first antibiotic dose should be recommended. However, the committee does feel that therapy should be administered as soon as possible after the diagnosis is considered likely. Conversely, a delay in antibiotic therapy has adverse consequences in many infections. For critically ill, hemodynamically unstable patients, early antibiotic therapy should be encouraged, although no prospective data support this recommendation. Data from the Medicare database indicated that antibiotic treatment before hospital admission was also associated with lower mortality [109]. Important for discharge or oral switch decision but not necessarily for determination of nonresponse. Patients should be switched from intravenous to oral therapy when they are hemodynamically stable and improving clinically, are able to ingest medications, and have a normally functioning gastrointestinal tract. Patients should be discharged as soon as they are clinically stable, have no other active medical problems, and have a safe environment for continued care. Subsequent studies have suggested that even more liberal criteria are adequate for the switch to oral therapy. One study population with nonsevere illness was randomized to receive either oral therapy alone or intravenous therapy, with the switch occurring after 72 h without fever. The study population with severe illness was randomized to receive either intravenous therapy with a switch to oral therapy after 2 days or a full 10-day course of intravenous antibiotics. Time to resolution of symptoms for the patients with nonsevere illness was similar with either regimen. Among patients with more severe illness, the rapid switch to oral therapy had the same rate of treatment failure and the same time to resolution of symptoms as prolonged intravenous therapy. The need to keep patients in the hospital once clinical stability is achieved has been questioned, even though physicians commonly choose to observe patients receiving oral therapy for 1 day. Even in the presence of pneumococcal bacteremia, a switch to oral therapy can be safely done once clinical stability is achieved and prolonged intravenous therapy is not needed [270]. Such patients generally take longer (approximately half a day) to become clinically stable than do nonbacteremic patients. The benefits of in-hospital observation after a switch to oral therapy are limited and add to the cost of care [32]. Discharge should be considered when the patient is a candidate for oral therapy and when there is no need to treat any comorbid illness, no need for further diagnostic testing, and no unmet social needs [32, 271, 272].

Some radiographic features specific to PsA (eg, pencil-and-cup deformity, joint space widening, gross osteolysis, and ankylosis) were included in the scoring system, but others (eg, phalangeal tuft resorption, juxta-articular and shaft periostitis) were not. Inhibition of radiographic progression was maintained in patients who continued on Enbrel during the second year. Improvements in physical function and disability measures were maintained for up to 2 years through the open-label portion of the study. Patients with complete ankylosis of the spine were excluded from study participation. Patients taking hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, or prednisone ( 10 mg/day) could continue these drugs at stable doses for the duration of the study. Responses were similar between those patients receiving concomitant therapies at baseline and those who were not. Patients with guttate, erythrodermic, or pustular psoriasis and patients with severe infections within 4 weeks of screening were excluded from study. After 3 months, patients continued on blinded treatments for an additional 3 months during which time patients originally randomized to placebo began treatment with blinded Enbrel at 25 mg twice weekly (designated as placebo/Enbrel in Table 13); patients originally randomized to Enbrel continued on the originally randomized dose (designated as Enbrel/Enbrel groups in Table 13). After 3 months of randomized, blinded treatment, patients in all three arms began receiving open-label Enbrel at 25 mg twice weekly for 9 additional months. Keep the product in the original carton to protect from light until the time of use. The dose tray containing Enbrel (sterile powder) must be refrigerated at 2 to 8C (36 to 46F). The healthcare provider should ask the patient questions to determine any risk factors for treatment. Patients developing signs and symptoms of infection should seek medical evaluation immediately. Physicians should instruct their patients to read the Medication Guide before starting Enbrel therapy and to reread each time the prescription is renewed. Infections Inform patients that Enbrel may lower the ability of their immune system to fight infections. Advise patients of the importance of contacting their doctor if they develop any symptoms of infection, tuberculosis or reactivation of hepatitis B virus infections. Other Medical Conditions Advise patients to report any signs of new or worsening medical conditions, such as central nervous system demyelinating disorders, heart failure or autoimmune disorders, such as lupus-like syndrome or autoimmune hepatitis. Advise patients to report any symptoms suggestive of a pancytopenia, such as bruising, bleeding, persistent fever or pallor. Allergic Reactions Advise patients to seek immediate medical attention if they experience any symptoms of severe allergic reactions. Advise latex-sensitive patients that the needle cap of the prefilled syringe and SureClick autoinjector contains dry natural rubber (a derivative of latex), which should not be handled by persons sensitive to latex. The first injection should be performed under the supervision of a qualified healthcare professional. Patients and caregivers should be instructed in the technique, as well as proper syringe and needle disposal, and be cautioned against reuse of needles and syringes. A puncture-resistant container for disposal of needles, syringes and autoinjectors should be used. If the product is intended for multiple use, additional syringes, needles and alcohol swabs will be required. To schedule any radiology exam please call Radiology Scheduling at 314-362-7111 or 877-992-7111, 7 a. Only the alpha- and betacoronavirus genera include strains pathogenic to humans (Paules, C. The first known coronavirus, the avian infectious bronchitis virus, was isolated in 1937 and was the cause of devastating infections in chicken. The first human coronavirus was isolated from the nasal cavity and propagated on human ciliated embryonic trachea cells in vitro by Tyrrell and Bynoe in 1965. However, coronaviruses have been present in humans for at least 500-800 years, and all originated in bats (Chan, P. The first four are endemic locally; they have been associated mainly with mild, selflimiting disease, whereas the latter two can cause severe illness (Zumla, A. Given the high prevalence and wide distribution of coronaviruses, their large genetic diversity as well as the frequent recombination of their genomes, and increasing activity at the humananimal interface, these viruses represent an ongoing threat to human health (Hui, D. The virus, provisionally designated 2019-nCoV, was isolated and the viral genome sequenced.

The most common valvular lesion is degenerative aortic stenosis followed by mitral regurgitation. Preoperative physical examination demonstrated a 4/6 systolic ejection murmur, but the emergent nature of the case dictated immediate operative intervention without cardiac work up. Transthoracic echo demonstrated aortic valve gradient of 55 mmHg and valve surface area of 0. Recent advancements in surgical and non-invasive techniques have allowed many, who were previously considered inoperable, the opportunity for surgical repair. It is common for multiple disorders to coexist, making management even more challenging. Patients with an existing valvular heart lesion who present with an acute insult (systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis, hemorrhage, etc. The following discussion aims at providing basic understanding of the causes of valvular heart disorders that are frequently encountered in critically ill patients, as well as diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Pathophysiology In the elderly, degenerative calcification causes thickening and or fusion of the valve leaflets. Persistent contraction against a fixed resistance stimulates hypertrophy of the left ventricular wall resulting in diastolic dysfunction. Physical exam findings include: soft ejection murmur, diminished aortic component of S2, and pulsus parvus et tardus. Doppler echocardiography can be used to assess the severity by measuring maximum jet velocity and mean transvalvular gradient, which allows calculation of aortic valve area. Left heart catheterization can be used to calculate transvalvular gradient and valve area. An alpha agonist such as phenylephrine is the agent of choice in the setting of hypotension since it maintains diastolic filling time by reflexively lowering the heart rate. Norepinephrine might be advantageous in patients with decreased ejection fraction due to its beta-1 activity. Maintaining sinus rhythm and avoidance of tachycardia are important to maximize filling time and cardiac output. Thus, immediate cardioversion is necessary in the setting of supraventricular arrhythmias causing hemodynamic instability. Percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty may also be considered, although it is typically done for palliation in patients too frail for any of the aforementioned interventions. Pathophysiology Aortic regurgitation can develop in two ways: abnormalities of aortic valve leaflets (calcific degeneration, bicuspid valve, destruction from endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease) and aortic disease (aneurysm of ascending aorta, aortic dissection). Physical findings include a diastolic murmur, wide pulse pressure, and diastolic hypotension. Echocardiography may demonstrate thickened valve leaflets, flail leaflets, a prolapsed valve, vegetations, and/ or aortic root dilatation. Echocardiography will show a regurgitant jet across the aortic valve on color flow Doppler. Management Afterload reduction is paramount in order to maintain cardiac output, reduce left ventricular wall stress, and reduce the regurgitant fraction. Inflation of the balloon during diastole will cause massive overload to the left ventricle causing acute decompensation. Pathophysiology Rheumatic heart disease is the most common cause of mitral stenosis. This leads to underfilling of the left ventricle with pressure and volume overload of the left atrium. Chronic underfilling of the left ventricle may lead to myocardial atrophy, wall thinning, and reduced systolic function. Chronic pressure and volume overload of the left atrium may lead to atrial fibrillation, pulmonary congestion, and pulmonary hypertension. Diagnosis Symptoms include signs associated with pulmonary congestion, including dyspnea, orthopnea, and coughing. Management Acute decompensation usually presents with an inciting event such as pregnancy, sepsis, or new onset atrial fibrillation. Pulmonary congestion is a hallmark feature and is treated with diuretics and respiratory support. Atrial fibrillation must be controlled and anticoagulation should be initiated, if indicated.