"Buy 20mg rabeprazole mastercard, gastritis symptoms images".

C. Ugolf, M.B. B.CH. B.A.O., M.B.B.Ch., Ph.D.

Co-Director, University of North Texas Health Science Center Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine

Adjusting to vision loss is an emotional process and clients must find ways to express their feelings and adapt to this radical change (Kinash, 2006). Once the client begins to use the other senses and find alternative ways of doing activities, however, life can return to normal (Guide Dogs for the Blind, 1999). The period of greatest emotional stress usually occurs at the onset of visual loss. While sudden loss of vision is extremely traumatic, it may be easier to cope than the uncertain, slow visual loss seen in many chronic ocular diseases. Age plays an important part in the way the person reacts emotionally to loss of sight. Younger people are more resilient from the severe emotional sequelae generated by loss of sight. Middle-aged individuals are at greater risk of having severe psychological difficulty, perhaps because of other stresses associated with changes occurring during mid-life. Another variable is the overall degree of visual loss; the more profound the visual loss, the slower and more challenging the adjustment (Crandell, Jr. Denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance are the major steps of reaction to visual loss. Not everyone goes through all the stages or in this order (Kubler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). Carroll (1961) outlined secondary losses that occur with loss of sight, including diminished physical integrity, decreased visual contact with the environment, loss of a means of communication, and reduced mobility. The sighted person easily recognizes distant object characteristics including size, shape, position, speed, and direction; persons with visual impairment have lost part or all of this recognition ability. Unless other cues exist, the individual is limited in contact to the more immediate environment (Crandell, Jr. Body language, facial expressions, and shadows suggesting time of day are missing when a person no longer has vision. Both physical and psychological factors are important when defining functional status of the individual with visual impairment. A person with total visual loss but with newly acquired competencies may still achieve physical, emotional, and financial independence, as well as social integration (Kinash, 2006). Inability to perform essential tasks, such as reading, driving, and recognizing faces poses barriers to successful employment, along with fatigue, depression, and anxiety. Orientation and mobility specialists train clients to navigate with the assistance of white canes or guide dogs, stressing the importance of adaptive skills, such as listening to traffic flow to determine when it is safe to cross a street. Factors that contribute to the degree of orientation and mobility include residual vision, age at onset of visual loss, posture and balance, intelligence, body image, space orientation, auditory tactile abilities, and personality (Panek, 2002). Substantial loss of peripheral field of vision is more debilitating than loss of central vision (Windsor & Windsor, 2001). A white cane is the primary mobility aid used by persons who are blind or visually impaired. It is recommended that training begin following diagnosis; yet, clients with some progressive eye disorders may decide to wait until vision loss impacts mobility. Those in need of aid must first acknowledge loss of vision to be comfortable using a white cane, a clear identifier of a person with vision impairment both to the individual and others. Clients are taught to walk safely down the street by rhythmically touching the tip of the cane side-to-side in front of them to obtain advanced knowledge of what is ahead. While some people prefer to use a red-tipped white cane for ambulation, many feel more comfortable relying on a guide dog (Guide Dogs for the Blind, 1999). Traveling with a guide dog differs from using a cane in that the dog navigates around obstacles, stops for stairs and other changes in elevation, and avoids overhead obstructions. The guide dog and owner work together as a team; the person needs to know the destination and how to get there to carefully instruct the dog. Vocational Adjustment As with daily living skills, vocational skills are a major component of successful independent functioning. Components of adjustment to visual loss, which include actual physical vision, orientation mobility, daily living, and vocational skills all interconnect during complex life events. In addition to remaining visual capabilities, those with visual impairment can function independently by using physical dexterity, non-visual job skills, natural talents, 180 Takeshita et al. These competencies, besides residual vision, help the patient enhance self-esteem and quality of life.

As indicated earlier, a sustained, coordinated bank and turn can easily be perceived as straight and level flight. If this occurs, a view from wing-high wide of the aircraft could place the moon and stars considerably below the erroneously perceived horizontal (Figure 3-12). In a coordinated bank and turn, the pilot may see the moon and stars below the apparent horizontal. This can produce a momentary illusion of nearly inverted flight and lead to erroneous movements. Dynamic Visual Stimulation Large moving visual fields (visual angle greater than 30 degrees) can induce the sensation of body motion within three seconds and also substantial sensations of body tilt (Brandt, Dichgans, & Koenig, 1973; Brandt, Wist, & Dichgans, 1971; Dichgans, Held, Young, & Brandt, 1972). Of considerable interest are apparently related findings that large moving visual fields modulate neural activity in the vestibular nuclei even when the head and body remain stationary (Dichgan, Schmidt, & Graf, 1973; Young & Finley, 1974). In lower animals, vestibular stimulation modulates responses in central visual projection fields even when the retinal image is fixed (Bisti, Maffei, & Piccotino, 1974; Grusser & Grusser-Kornehls, 1972; Horn, Steckler, & Hill, 1972). These various results point to the intimate relations between the visual and vestibular systems in both the "feed forward" and "feedback" loops involved in the control of whole-body motion. Such effects could influence the pilot in high-speed, low-level flight, or in any of several situations. A visually induced illusion appears to have been important in the following disorientation accident involving the loss of an aircraft. The unidirectional streaming of the peripheral visual field was therefore almost ideal for inducing sensations of whole-body turning to the right. As the student shifted his attention to his cockpit instruments, he experienced a strong illusory sensation of right bank and turn, although he was in fact in level flight. Following an erroneous corrective action based on his false perception, the student, now at fairly low altitude, ejected from his aircraft. The conditions were adequate to set up a normal illusory reaction to an unusual motion condition: the pilot had just transitioned from an external reference to instrument flight; the pilot was relatively inexperienced and fatigued; altitude and proximity of another aircraft provided little time for corrective actions. Probability of disorientation is high when pilots keep station on another aircraft. Flicker Vertigo Flashing light from sun rays or shadows reflecting from helicopter rotors or from blades of propeller driven, fixed wing aircraft can be very disconcerting, and, in exceptional cases, epileptiform seizures have resulted. In prop planes, the phenomenon may be strongest while the aircraft is taxiing into the sun so that the blades are rotating at relatively low rpm, and intense light flashes may be reflected into the eyes. In a helicopter survey, 35 percent of the pilots responding reported disturbance by flicker from rotors, but 70 percent reported difficulties arising from reflections from the anticollison light (Tormes & Guedry, 1975). Perception of Vertical Linear Acceleration Misjudgment of helicopter motion during hover was found to be a prominent factor in a number of disorientation incidents during conditions of poor external visibility. Moreover, extraneous motion stimuli such as a visible "salt" spray through rotor blades, wave motion, ship motion during night landings, and even wind currents in the cockpit can exacerbate the situation in naval helicopter operations (Tormes & Guedry, 1975). Vertical linear oscillations introduce linear accelerations that are aligned with gravity so that the magnitude of the resultant force field changes relative to the head, but its direction does not. If an erect observer is oscillated vertically, the changing linear acceleration is approximately perpendicular to the utricular otolith plane, and, therefore, it is ineffective as a utricular stimulus. Its approximate alignment with the saccular otolithic plane would introduce an effective saccular "shear" stimulus, but the saccular otoliths, already deflected by a 1 g shear force, may be relatively insensitive to added acceleration in the same plane. Walsh (1964) reported large stimulus response phase errors (individuals experienced maximum downward travel during upward travel) at 0. If methodological differences and stimulus artifacts influence perceptual consistency in formal experiments, the pilot will also be subject to perceptual inconsistencies and occasional large phase errors in the noisy acceleration environment of flight where he is variously occupied with different elements of his flight task. Prevention of Disorientation Disorientation of flight will be experienced at one time or another by all pilots who fly more than a few hours under conditions of poor visibility. However, the intensity of the experience, the ease with which it is resolved, and the frequency vary. Some pilots may be aware of disorientation on every flight while others are rarely troubled (Aitken, 1962). About 58 percent of the helicopter pilots questioned by Tormes and Guedry (1975) indicated one or more episodes of severe disorientation.

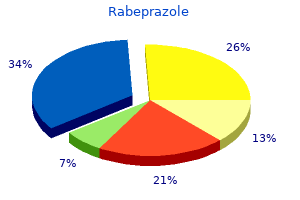

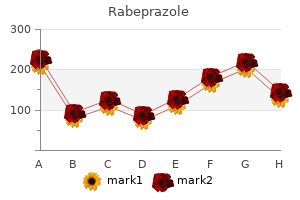

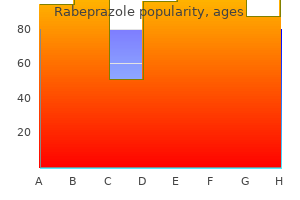

Table 1 indicates that in 1970, 5,022 out of the 562,887 white women in Miami died, and that 285 of the 106,917 white Alaskan women died. Although the crude rates suggest that the force of mortality is stronger in Miami than in Alaska, Table 1 reveals that for any given age the two populations have very similar mortality rates. Compared to Alaska, Miami has a much greater proportion of women in older age groups, where mortality is high. Since the data from larger strata dominate the crude death rate, the Miami death rate is heavily influenced by the high mortality in older ages. In contrast, in Alaska the crude death rate reflects the low mortality rates among young women, who account for a much larger proportion of the Alaska population than they do of the Florida population. Two populations may have the same overall size and identical age-specific death rates, but different total numbers of deaths and different overall death rates, due to differences in their age distributions. Standardization (and other adjustment procedures) seeks to provide numbers and comparisons that minimize the influence of age and/or other extraneous factors. It follows intuitively that if Miami had the same age distribution as Alaska, or vice-versa, their crude death rates would be similar to each other. As a matter of fact, if Miami and Alaska had the same age distribution, regardless of what that distribution might be, their crude death rates would be similar, since their age-specific rates are similar. In direct standardization the stratum-specific rates of study populations are applied to the age distribution of a standard population. In other words, direct standardization applies the same set of weights to the age-specific rates of Alaska and Miami, and the summary (age-adjusted) death rate is therefore independent of differences in the age distribution of the two populations. The directly age-standardized death rates are equivalent to the crude death rates which Miami and Alaska "would have experienced" if they had had the same age distribution as the 1970 U. This formula shows that, when the same standard is used, if two study populations have the same age-specific rates. Some points to consider There are several things to consider about the above formula and computation. Since each Wk is the proportion that the k-th stratum is of the total standard population, the weights are simply the proportional age distribution in the standard population. Similarly, a directly standardized rate corresponds to the crude rate that would be observed in the standard population if the standard population had the same stratum-specific rates as does the study population. Unless the death rates are the same across all age strata or the changes in person-years do not change the proportional age distribution, then hypothetical statements such as "if the U. First, summary indices from two or more populations are more easily compared than multiple strata of specific rates. When sample populations are so small that their strata contain mostly unstable rates and zeroes, the direct standardization procedure may not be appropriate and an alternate procedure (see below) becomes desirable. Although standardized rates can summarize trends across strata, a considerable amount of information is lost. For example, mortality differences between two populations may be much greater in older ages, or rates for one population compared to another may be lower in young ages and higher in older ages. In the latter case, a single summary measure obscures valuable information and is probably unwise. Furthermore, different standards could reverse the relative magnitude of the standardized rates depending on which age groups were weighted most heavily. The trade-off between detailed information and useful summarization runs through epidemiologic data analysis methods. Simultaneous adjustment Rates can be standardized for two or more variables simultaneously. The combined population is used as the standard to adjust for age and baseline blood pressure differences in the two weight categories. Computations for simultaneous adjustments are essentially identical to those for the single case: Standardized rate for low weight subjects = [(0. Baseline Diastolic Blood Pressure - Low Normal Moderate Low Normal Moderate Relative weight - Light Heavy Total - - - No. Indeed, spreadsheets are a very convenient method for carrying out a modest number of standardizations. Spreadsheet neophytes will certainly want to learn this method, and even experienced spreadsheet users (who will no doubt want to try this on their own before reading further) may find that creating an age standardization worksheet helps them to learn and understand standardization methods better. To create the above table in a spreadsheet program, copy the layout, the columns and rows that contain the labels ("35-44", "Moderate", "Light", etc. I will assume that the first row of data (for ages 25-34 years, low diastolic blood pressure) is row 14 (allowing some blank rows for labels and documentation).

A7148 Predictors and Pathology of Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis/Y. A7154 the Impact of High Versus Low Mean Arterial Pressure Goals in Cirrhotic Patients with Septic Shock/A. A7155 Vasopressor Dosing in Septic Shock Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis/B. A7157 Risk Factors for Infection and Evaluation of Sepsis-3 in Patients with Trauma/E. A7158 A Machine Learning Approach to Sepsis Prediction in non-Intensive Care Unit Patients/A. A7159 An Investigation of Emergency Treatment of Sepsis-Clinical Intervention Prediction Using Machine Learning Models/X. A7160 Impaired Forearm Reactive Hyperemia Is Associated with Lactate, Red Blood Cell Deformability, and Mortality in Septic and Non-Septic Critically Ill Patients/C. A7161 Monocyte Distribution Width, an Early Indicator of Sepsis-3 in High Risk Emergency Department Patients/E. A7164 Blood Filtration Using Dialysis-Like Therapy Attenuates Organ Injury in Nonhuman Primates with Severe Streptococcus Pneumoniae Sepsis/L. A7167 Illness Severity Scores in an Ethiopian Medical Intensive Care Unit: A Preliminary Comparison of Models Tailored to Lowand Middle-Income Settings/D. A7168 Evaluating Performance in Protocol-Driven Sepsis Management: New Measures/S. A7169 Increased Mortality in Severe Sepsis Patients Who Presented to the Emergency Department During the Night Shift/T. A7170 Prehospital Characteristics of Clinical Sepsis Phenotypes Identified at Emergency Department Presentation/E. A7171 Front Line of Sepsis Care: Training Emergency Medical Services Providers to Identify Sepsis Using a Validated Sepsis Screening Tool/K. A7173 Protocol-Driven Sepsis Management: Single Hospital System Analysis of Compliance and Outcome/R. A7177 Breathing Counts: Addressing Barriers to Medication Use in High Risk Children with Asthma/H. A7180 Overweight and Obesity are Associated with Higher Tidal Volumes in Children with Asthma/R. A7181 Objective Discharge Criteria Results in 48% Lower Readmission Rates for Children with Status Asthmaticus/S. A7182 Predictors of Return Acute Asthma Visits Among Patients Receiving Guideline Recommended Discharge Management in the Emergency Department/D. A7184 Evaluation of Non-Invasive Nasal Immune Mediator Biomarkers of Asthma Control/M. A7185 Utility of Salivary Cortisol in Corticotropin Releasing Hormone Test in Asthmatic Children/Y. A7186 Eosinophil Phenotypes in Children with Asthma: Association with Asthma Control/S. A7187 Low Levels of Bronchoalveolar Lavage Soluble Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products Is Associated with Increased Serum Eosinophils and IgE Levels in Children with Asthma/J. A7189 Nasopharygeal Airway Microbiome in Children with Asthma and Resistant Airway Obstruction/S. A7191 the Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Mepolizumab in Children from 6 to 11 Years of Age with Severe Eosinophilic Asthma/J. A7478 Genetic Variation at the 17q21 Locus Is Associated with Altered Sphingolipids in Children/J. A7197 A Microrna96 Mimic Delivered Direct to the Lungs Can Reverse Sugen/Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension in the Rat/C. A7198 Overexpression of miR125b Induces Group3 Pulmonary Hypertension in Pre-Existing Pulmonary Fibrosis/S. A7201 Biomarker Diagnostics for Pulmonary Hypertension: Studies in Management by Exercise Training or Nightly Oxygen/G. A7204 Examining the Impact of Endothelial Bone Morphogenic Protein Receptor 2 Loss on Interleukin-15 Signaling and the Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension/L.