"20mg simvastatin, cholesterol medication does not affect liver".

H. Shawn, M.B. B.CH. B.A.O., Ph.D.

Medical Instructor, University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine

Aspergillosis (see Chapter 401) of the pleura is uncommon, but an inflammatory, thickened pleura is frequently seen in progressive invasive aspergillosis. Pleural effusions due to parasitic diseases are uncommon but increasing among Third World immigrants. Frank blood in the pleural space (hematocrit >20%) is usually the result of trauma, hematologic disorders, pulmonary infarction, or pleural malignancies. Left-sided pneumothorax, particularly with a widened mediastinum, may indicate rupture of the aorta. Pleural blood often does not clot and can be readily removed by lymphatics if the volume is small. Leakage of the lymph (chyle) from the thoracic duct most commonly results from mediastinal malignancy (50%), especially lymphoma. The triad of slow-growing yellow nails, lymphedema, and pleural effusion (yellow-nail syndrome) is due to hypoplastic or dilated lymphatics. Because chyle collects within the posterior mediastinum, the chylothorax may not appear for days, until the mediastinal pleura ruptures. The usual milky appearance of the effusion may be confused with a cholesterol effusion or an effusion with many leukocytes. The best diagnostic criterion for chylothorax is the presence of a triglyceride concentration greater than 110 mg/dL, with rare instances of values between 50 and 110 mg/dL. The major complications are malnutrition and immunologic compromise, as fat, protein, and lymphocytes are depleted with repeated thoracentesis or chest tube drainage. Treatment should include drainage of the pleural space and attempts to decrease chyle formation by intravenous hyperalimentation, decreased oral fat intake, and intake of medium-chain triglycerides, which are absorbed directly into the portal circulation. For traumatic effusions, thoracic duct ligation should be considered; when due to tumor, treatment should focus on the primary cause. Clinical pleurisy occurs in close to 5% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (see Chapter 286), even though autopsy studies suggest up to 50% involvement. It has a male predominance and appears within 5 years after onset of the disease; nevertheless, effusions have occurred up to 20 years before the onset of articular disease. The effusion does not resolve quickly but rather over months and occasionally persists over years. Pleuritic pain or effusion can be the presenting manifestation in 5% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and occurs at some point in the course in up to 50% of patients. Pain (86%), cough (64%), dyspnea (50%), pleural friction rub (71%), and fever (57%) are common. The effusions are exudates that in the majority of cases have normal pH and glucose. Lupus pleuritis is likely if the antinuclear antibody ratio in the fluid is more than 1:160. Spontaneous resolution of lupus pleuritis is uncommon, but it usually disappears within 2 weeks after beginning therapy with corticosteroids. Asbestosis (see Chapter 78) is frequently associated with pleural disease; the effusion is often unilateral, small, and serosanguineous. Exclusion of malignant mesothelioma in the presence of pleural plaques may be difficult and requires follow-up every 2 to 3 years. The effusion tends to resolve in 1 month to 1 year, leaving a blunted costophrenic angle in more than 90% of patients and diffuse pleural thickening in about 50%. Most commonly seen after menopause, the symptoms are malaise, chest pain, and increased abdominal girth. Uremia causes a polyserositis and usually a bloody pleural exudate that resolves with treatment of the uremia. The diagnosis must be distinguished from a urinothorax or a hydrothorax caused by the nephrotic syndrome. Repeated thoracentesis may be needed if the patient is symptomatic (dyspnea, cough, chest pain). Other causes of inflammatory effusions include radiation therapy, esophageal sclerotherapy, enteral feeding misplacement, and drug-induced pleural disease from medications such as nitrofurantoin, dantrolene, methysergide, methotrexate, procarbazine, amiodarone, mitomycin, bleomycin, and minoxidil. Pleuritis with a lupus-like syndrome has been associated with procainamide, hydralazine, isoniazid, and quinidine; signs and symptoms usually resolve after discontinuing the medicine but may occasionally require corticosteroids. Malignant effusions probably are the most common cause of exudate in patients older than age 60. Invasion by lung cancer is the most frequent, whereas spread from liver metastasis or chest wall lymphatic invasion is the most frequent mechanism in breast cancer.

Particularly when combined with other prothrombotic mutations (multigene interactions), these primary hypercoagulable states are associated with a lifelong predisposition to thrombosis. The trigger for a discrete, clinical thrombotic event is often the development of one of the acquired, secondary hypercoagulable states superimposed on an inherited state of hypercoagulability. The secondary hypercoagulable states, a diverse group of mostly acquired conditions. Antithrombin is the major physiologic inhibitor of thrombin and other activated coagulation factors, and its deficiency leads to unregulated protease activity and fibrin formation. Patients with type I antithrombin deficiency have proportionately reduced plasma levels of antigenic and functional antithrombin that result from a quantitative deficiency of the normal protein. Impaired synthesis, defective secretion, or instability of antithrombin in type I antithrombin-deficient individuals is caused by major gene deletions, single nucleotide changes, or short insertions or deletions in the antithrombin gene. Most affected individuals are heterozygotes whose antithrombin levels are typically about 40 to 60% of normal but may have the full clinical manifestations of hypercoagulability. The frequency of asymptomatic heterozygous antithrombin deficiency in the general population may be as high as 1 in 350. Most of these individuals have clinically silent mutations and will never have thrombotic manifestations. The frequency of symptomatic antithrombin deficiency in the general population has been estimated to be between 1:2000 and 1:5000. Among all patients seen with venous thromboembolism, antithrombin deficiency is detected in only about 1%, but it is found in about 2. In type I, frameshift, nonsense, or missense mutations cause premature termination of protein synthesis or loss of protein stability. Relatively few specific mutations of the protein S gene have been described to date, most involving frameshift, nonsense, or missense point mutations. However, its frequency among patients evaluated for venous thromboembolism (2 to 3%) is comparable to that of protein C deficiency. Heterozygosity for the autosomally transmitted Factor V Leiden increases the risk of thrombosis by a factor of 5 to 10, whereas homozygosity increases the risk by a factor of 50 to 100. The Factor V Leiden mutation is remarkably frequent (3 to 7%) in healthy white populations but appears to be far less prevalent or even non-existent in certain black and Asian populations. The pathophysiologic basis of thrombotic risk in these diverse disorders is complex and multifactorial. The substitution of G for A at nucleotide 20210 of the prothrombin gene has been associated with elevated plasma levels of prothrombin and an increased risk of venous thrombosis. This prothrombin gene mutation is found in 6 to 18% of patients with venous thromboembolism. A number of other inherited abnormalities of specific physiologic antithrombotic systems may be associated with a thrombotic tendency. However, most of these conditions are limited to case reports or family studies, their molecular genetic bases are less well defined, and their prevalence rates are unknown but are probably much lower than those of the disorders described above. Hyperhomocysteinemia is due to elevated blood levels of homocysteine, a sulfhydryl amino acid derived from methionine; when blood levels are sufficiently increased, particularly in homozygous children, homocystinuria develops. Homocysteine can be metabolized by either of two remethylation pathways (catalyzed by methionine synthase, which requires folate and cobalamin, or by betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase); alternatively, homocysteine is converted to cystathionine in a transsulfuration pathway catalyzed by cystathionine beta-synthase, with pyridoxine used as a cofactor. Inherited hyperhomocysteinemia is most commonly caused by deficiency of cystathionine beta-synthase, whereas a minority of cases are caused by hereditary defects in the remethylation pathways. Homozygous deficiency states that lead to severe hyperhomocysteinemia cause premature arterial atherosclerotic disease and venous thromboembolism, as well as mental retardation, neurologic defects, lens ectopy, and skeletal abnormalities. However, adults with heterozygous deficiency states, with resultant mild to moderate hyperhomocysteinemia, may have only venous or arterial thrombotic manifestations. The frequency of heterozygous cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency in the general population is 0. Acquired causes of hyperhomocysteinemia in adults most commonly involve nutritional deficiencies of the cofactors required for homocysteine metabolism, including pyridoxine, cobalamin, and folate. Acquired as well as inherited hyperhomocysteinemia is a likely risk factor for arterial and venous thrombosis. The mechanism of homocysteine-induced thrombosis and atherogenesis involves complex and probably multifactorial effects on the vessel wall.

Non-erosive oligoarthritis, without evidence of infection or other demonstrable cause, often resolves after institution of immunoglobulin therapy. Its resolution with treatment does not necessarily constitute a priori evidence of an infectious etiology. Intravenous gamma globulin treatment might suppress arthritis through its complex modulating effect on the immune system. It is painful, and there is often warmth, redness, and swelling; it favors large joints, and subcutaneous nodules have been noted in a few patients. Less often, small joints of the hands and feet are inflamed, and the arthritis becomes chronic and resembles rheumatoid arthritis. The synovial fluid white blood cell count is sometimes elevated to 50,000/mm3, and rod-shaped bacilli (Tropheryma whippelii) have been identified, usually by electron microscopy, in synovial biopsy specimens. Diagnosis is facilitated by polymerase chain reaction analysis of tissue or blood. Transient pain in the Achilles tendon appears to be more common than frank inflammatory tendinitis, which can last a few days and recur two or three times a year. A few patients have acute painful monoarthritis or pauciarthritis of the knees, ankles, or small joints that lasts a week or more and recurs frequently. Less common is an incapacitating polyarthritis resembling rheumatic fever, persisting a month or more. In one study, 40% of 73 heterozygous patients were symptomatic; articular manifestations appeared at times before the xanthomas that are the major diagnostic sign of familial hypercholesterolemia. Aches and stiffness simulating fibromyalgia may appear early in hypothyroidism; if untreated, this may progress to proximal myopathy with elevated creatine kinase levels, simulating polymyositis, or to a syndrome of synovial thickening and joint effusions, simulating rheumatoid arthritis. Carpal tunnel syndrome is a recognized manifestation of hypothyroidism, and there appears to be an association with calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease. Hyperthyroidism can cause myopathy without elevations of the creatine kinase level but with muscle wasting, which can be severe. Hyperparathyroidism is a rare cause of diffuse, vague musculoskeletal pains resembling those of fibrositis. The other musculoskeletal complications of hyperparathyroidism include back pain due to vertebral body fractures, an erosive arthritis predominantly in the hands and wrists, and chondrocalcinosis (with pseudogout occurring most often after parathyroidectomy). Carpal tunnel syndrome has been reported in almost one half of persons with acromegaly. Joint or juxta-articular pains are experienced by as many as one third of patients with acute sarcoidosis and may be the only symptom of the disease; however, erythema nodosum often accompanies the arthritis and, together with hilar adenopathy, suggests the diagnosis (one should be aware that arthritis may accompany erythema nodosum of any cause). The distal interphalangeal joints are typically spared, but any of the other peripheral joints, as well as the heels, may be painful out of proportion to signs of inflammation, which are meager. Episodes last a few days to a few months, and the arthritis usually resolves completely. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is often elevated; antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factors may be present in high titer. Progressive, deforming arthritis is a feature of chronic sarcoidosis, as are bone lesions, both lytic and sclerotic. Serositis, fever, and arthritis are the major signs of familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis occurs in as many as one half of patients; it is usually monoarticular and confined to large joints in the lower extremities. Although the arthritis usually lasts less than 1 week, it has been reported to persist for several months. Synovial fluid contains large numbers of granulocytes, and there is intense infiltration of granulocytes and hyperemia in synovial tissue. Diagnosis is suggested by demographic and other clinical features of the disease; criteria for diagnosis have been proposed and are based on the clinical features. In the absence of these, familial Mediterranean 1558 fever is easily confused with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Livneh A, Langevitz P, Zemer D, et al: Criteria for the diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever. The authors propose diagnostic criteria based on the major clinical manifestations of pleuritis, pericarditis, peritonitis, fever, and arthritis.

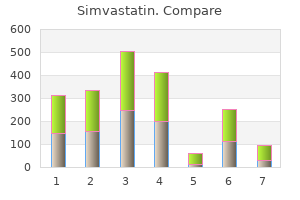

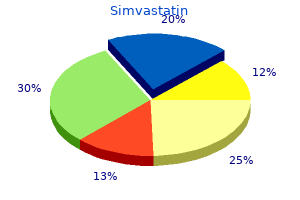

Screening tests for Bence Jones proteins (monoclonal light chain in the urine) that use their unique thermal properties are not recommended because of their serious shortcomings. Immunofixation of an adequately concentrated 24-hour urine specimen reliably detects Bence Jones protein. An M-protein appears as a dense, localized band on the agarose gel or a tall, narrow, homogeneous peak in the densitometer tracing, and its amount can be calculated on the basis of the size of the spike and the amount of total protein in the 24-hour specimen. It is not uncommon to have a negative reaction for protein and no obvious spike on electrophoresis and yet for immunofixation of a concentrated urine specimen to show a monoclonal light chain. Immunofixation should also be done on the urine of every adult older than age 40 who develops a nephrotic syndrome of unknown cause. The presence of a monoclonal light chain in nephrotic urine is strongly suggestive of primary amyloidosis or light chain deposition disease. The term benign monoclonal gammopathy is misleading because at diagnosis it is not known whether the process producing an M-protein will remain stable and benign or will develop into symptomatic multiple myeloma, macroglobulinemia, amyloidosis, or a related disorder. Because of this high prevalence, it is crucial to determine whether the M-protein will remain benign or will evolve to multiple myeloma, amyloidosis, macroglobulinemia, or another lymphoproliferative disease. Prognosis In one series of 241 patients followed long-term after a diagnosis of benign monoclonal gammopathy. Of note was that about 75% of the patients had other conditions that brought them to medical attention but that were seemingly unrelated to the monoclonal gammopathy. An M-protein was found in the urine in only 9 patients, and bone marrow plasma cells ranged from 1 to 10% (median, 3. Anemia, 979 Figure 181-3 A, Distribution of serum monoclonal proteins in 993 patients seen at the Mayo Clinic during 1996. B, Diagnoses in 1066 cases of monoclonal gammopathy seen at the Mayo Clinic during 1996. At follow-up, 24 to 38 years later, the 241 patients could be divided into four groups. Approximately one tenth of the patients have remained stable and could be classified as having benign monoclonal gammopathy, although they must continue to be observed because serious disease may still develop. No initial laboratory measurements or clinical factors were predictive of which patients would remain in this stable or benign group. In 11% of the patients, the M-protein level increased to more than 3 g/dL, but they did not develop symptomatic multiple myeloma, macroglobulinemia, or related disorders; their condition remained clinically "benign," although with an M-protein level that causes concern. More than half of the patients died of seemingly unrelated causes without developing multiple myeloma, macroglobulinemia, or related disorders. Approximately one fourth of the patients (26%) developed multiple myeloma (18%), macroglobulinemia (3%), amyloidosis (3%), or related disorders (2%), with an actuarial rate of 16% at 10 years, 33% at 20 years, and 40% at 25 years. The interval from the time of recognition of the M-protein to the diagnosis of serious disease ranged from 2 to 29 years (median, 10 years). In seven patients, multiple myeloma was diagnosed more than 20 years after detection of the serum M-protein. The association of a monoclonal light chain (Bence Jones proteinuria) with a serum monoclonal gammopathy suggests multiple myeloma or macroglobulinemia, but many patients with small amounts of monoclonal light chain in the urine have stable M-protein levels in the serum for many years. The presence of more than 10% plasma cells in the bone marrow suggests multiple myeloma, but some patients with more plasma cells have remained stable for long periods. The presence of osteolytic lesions strongly suggests multiple myeloma, but metastatic carcinoma may produce lytic lesions Figure 181-4 Incidence of multiple myeloma, macroglobulinemia, amyloidosis, or lymphoproliferative disease after recognition of monoclonal protein. The presence of circulating plasma cells in the peripheral blood usually indicates active multiple myeloma. However, no single technique reliably differentiates a patient with a benign monoclonal gammopathy from one who will subsequently have symptomatic multiple myeloma or other malignant disease. The M-protein level in the serum and urine should be serially measured, together with periodic re-evaluation of clinical and other laboratory features, to determine whether multiple myeloma or another related disorder is present. If an M-protein is present in the urine, the patient should be followed more closely by repeating serum and urine protein levels at 6-month intervals rather than annually. Association of Monoclonal Gammopathies with Other Diseases Monoclonal gammopathy frequently exists without other abnormalities. However, certain diseases are associated with it more often than expected by chance. An M-protein is found in 3 to 4% of patients with a diffuse lymphoproliferative process but in fewer than 1% of those with a nodular lymphoma. IgM monoclonal gammopathies are more common than IgG or IgA in lymphoproliferative diseases.