"Buy generic adcirca 20 mg on line, erectile dysfunction treatment in lahore".

I. Javier, M.A., M.D.

Professor, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine

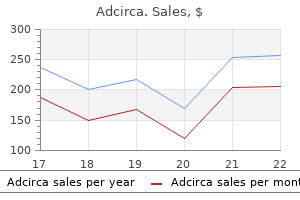

Each of these agents will be discussed in turn, followed by a discussion of an overall treatment strategy. Treatment with levodopa or dopamine agonists eventually causes significant neuropsychiatric side-effects. The monoamine oxidase inhibitors selegiline (used in doses of 10 mg or less daily) (Myllyla et al. Although perhaps controversial, there is also evidence that both selegiline (Palhagen et al. Anticholinergics, although useful for tremor, have a limited effect on bradykinesia and rigidity, and in some patients may cause confusion or a memory deficit. In light of this, they are generally reserved for cases in which tremor is prominent, with due regard for any emerging cognitive deficits. Given this limited benefit, and the side-effects seen with amantadine, routine use is probably not justified. There may, however, be a place for amantadine in the treatment of levodopa-induced dyskinesias (Verhagen Metman et al. When fluctuations appear, using lower and more closely spaced doses of levodopa may help, or one may add tolcapone. Attention should also be paid to the possibility of Helicobacter pylori infection; in patients with confirmed infection, successful treatment with omeprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin was followed by increased absorption of levodopa and increased on-time (Pierantozzi et al. As noted above, dopamine agonists include a number of different agents: although bromocriptine is the oldest member of this group, problematic side-effects, combined with the fact that newer agents. Of these dopamine agonists, cabergoline has been strongly associated with cardiac valvular disease (Zanettini et al. When dopamine agonists are used, patients should be cautioned that sleep attacks may occur (Avorn et al. The optimum overall treatment strategy is still a matter of some debate, and although the strategy recommended here is intended as a middle of the road approach, not all authors will be in agreement. In mild cases one may begin with one of the monoamine oxidase inhibitors and, when tremor is prominent, some clinicians advocate the use of an anticholinergic. With disease progression, however, one must at some point add either levodopa or a dopamine agonist, and the question of which to use first has not been settled. Given the sometimes stunning effectiveness of levodopa, some advocate using this first, especially when a prompt response is required, for example when a patient is threatened with job loss. Others, however, with an eye towards delaying the emergence of levodopa-induced dsykinesias, advocate starting with dopamine agonist monotherapy and adding levodopa only as the disease progresses. All other things being equal, it may be prudent to begin with a dopamine agonist, either pramipexole or ropinirole, increasing the dose as required until limiting side-effects occur or further dose increases are not effective, and then, with disease progression, to add levodopa. When fluctuations in levodopa responsiveness begin to appear, the addition of tolcapone may be considered. If one begins with levodopa rather than with dopamine agonist monotherapy, at some point one will generally have to add a dopamine agonist to smooth out the effect of levodopa and to allow a dose reduction and a reduction in levodopainduced dyskinesias. In treating patients with levodopa or dopaminergic agents, it is important to avoid suddenly stopping them as this may precipitate a neuroleptic malignant syndrome, as has been reported for levodopa (Sechi et al. Most patients treated with levodopa or dopamine agonists will eventually develop significant neuropsychiatric side-effects. The most common of these are visual hallucinations; others include psychosis, anxiety (during wearing off of levodopa), and certain other, much less common, phenomena, including impulsive behaviors, stereotypies, euphoria (with, rarely, mania), and delirium. Visual hallucinations are very common with prolonged treatment with either levodopa or dopamine agonists: in one 6-year study, the percentage of patients with hallucinations gradually increased until, at the end of the study, fully 62 percent were experiencing them (Goetz et al. Auditory hallucinations, or even olfactory or gustatory hallucinations, may also occur, but these are much less common (Goetz et al. Furthermore, it appears that patients with greater cell loss and Lewy body pathology in the amygdala are more likely p 08.

Agents capable of causing a modest symptomatic improvement include the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors donepezil (Feldman et al. As noted above, there is a correlation between the loss of cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis of Meynert and memory loss, and it is probably by partly restoring cholinergic tone that the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors exert their therapeutic effect. Importantly, with treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, one sees not only some cognitive improvement but also some improvement in other clinical features, such as mood changes and, in some cases, delusions or hallucinations. The optimum strategy with regard to these medications has not as yet been established. In my opinion it is reasonable to begin with a cholinesterase inhibitor, for example donepezil, and then monitor for a matter of months; if there has been some improvement but, as is usually the case, there is room for further improvement, memantine may then be added. The place of d-cycloserine and Gingko biloba has simply not been elucidated; however, during a time of relative clinical stability, one may consider adding one of these. Other symptoms that may respond to pharmacologic treatment include depression, insomnia, apathy, agitation, and delusions and hallucinations. Insomnia may, of course, be part of a depressive syndrome and, as such, may eventually respond to treatment with an antidepressant; in cases in which a hypnotic is required, consideration may be given to melatonin or zolpidem. Although quetiapine has been associated with sedation, in my experience this agent, if started at a low dose. With regard to the use of antipsychotics, concern has been raised that they may accelerate cognitive decline; however, at least in the case of risperidone, this does not appear to be the case (Livingston et al. Delusions and hallucinations, whether accompanied by agitation or not, may respond to the same antipsychotics as used for agitation; however, as with all symptoms, one must be sure that these delusions or hallucinations are sufficiently troubling to warrant the risk attendant on the use of antipsychotics. Clinical features the onset is gradual and insidious, typically occurring in the fourth through the seventh decades; onsets as young as 21 (Lowenberg et al. In most cases, the presentation is with a personality change, typically of the frontal lobe type, with disinhibition, coarsening of behavior, and perseveration (Bouton 1940; Ferraro and Jervis 1936; Litvan et al. Eventually, cognitive deficits appear, such as short-term memory loss, concreteness, and difficulty with calculations; in many cases an aphasia, typically of the expressive type, will supervene, and, in a small minority, seizures may occur. Interestingly, even when the temporal lobes are very hard hit, the posterior two-thirds of the superior temporal gyrus is generally spared, often to a remarkable degree, as illustrated in Figure 8. Although in most cases both the frontal and the temporal lobes are clearly affected, in a minority only one lobe will be macroscopically abnormal (Sjorgen et al. Pick cells (large, ballooned neurons) and Pick bodies (rounded or oval argentophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions) may be seen in affected areas; the Pick bodies are composed of neurofilaments that are p 08. The syndrome itself, as noted below, is characterized initially by a personality change, with, in most cases, the eventual development of a dementia. Frontotemporal dementia, among the neurodegenerative disorders, is a relatively common cause of dementia. Most of these familial cases are associated with mutations in the tau gene (Bronner et al. The frontal variant, as might be expected, is characterized by the frontal lobe syndrome, with varying mixtures of disinhibition, mood changes, perseveration, and overall coarsening of behavior; some patients may become quite gluttonous and some will show a pronounced taste for sweets. In some cases the environmental dependency syndrome may occur; as discussed in Section 4. Over time, and well after the personality change has become established, a dementia supervenes, which, however, may remain relatively mild. Judgment and abstract thinking fail, and eventually there may be amnestic features. Tumors of the frontal or temporal lobes may mimic these disorders, but are immediately identified by imaging. Uncommonly, frontotemporal dementia may present with an expressive aphasia (Bak et al. Tumors of the frontal or temporal lobes may cause a similar presentation but are immediately identified on imaging.

Importantly, many patients with tardive dystonia will also have choreiform movements (Sachdev 1993a; Wojcik et al. Pain represents the rarest expression of tardive dyskinesia, and patients may complain of burning pain in the mouth or genital area; this typically occurs in the setting of choreiform movements or akathisia (Ford et al. In the remainder, however, only a partial remission occurs, after which the abnormal movements persist indefinitely. This chronic course is more likely in the elderly and in those who have been treated with very high doses. Interestingly, choreiform movements in tardive dyskinesia are worsened by anticholinergics (Greil et al. Patients who develop a depressive syndrome typically experience a worsening of symptoms (Sachdev 1989), whereas during mania there may be a partial remission (de Potter et al. Etiology Although the vast majority of cases of tardive dyskinesia occur secondary to treatment with antipsychotics, cases have also been reported with other dopamine blockers, such as metoclopramide (Sewell and Jeste 1992; Sewell et al. Given that all of the drugs capable of causing tardive dyskinesia have one thing in common, namely a blockade of post-synaptic dopamine receptors, and given that the risk of tardive dyskinesia increases with higher doses (Morganstern and Glazer 1993) and a longer duration of treatment (Glazer et al. Further support for a disturbance in dopamine transmission is provided by the response to anticholinergics in tardive dyskinesia. Dopaminergic and cholinergic systems exist in a balance in the basal ganglia, such that an increase in dopaminergic tone may be mimicked by a reduction in cholinergic tone and vice versa. Given this one would predict that, in patients with tardive dyskinesia, a reduction in cholinergic tone, as might occur with the administration of an anticholinergic medication, would increase the abnormal movements, and this is generally what happens (Klawans and Rubovits 1974). As attractive as this dopamine theory is, it does not account for several important findings. First, the fact that acute antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism can co-exist with Course the course of tardive dyskinesia has been most thoroughly studied with reference to the choreiform type. In situations in which the antipsychotic is continued at a constant dose, there is a gradual worsening of symptoms; although in most cases the severity eventually reaches and stays at a plateau, in a minority one sees a relentless progression (Gardos et al. If the antipsychotic is discontinued there is typically a pronounced worsening of symptoms, which is followed, however, over the succeeding weeks or months, by at least some diminution of symptoms, after which one of two eventualities may ensue (Glazer et al. Second, some cases of the dystonic subtype of tardive dyskinesia may, as noted below, be relieved by, rather than worsened by, anticholinergic agents. Unfortunately for the theory, however, tardive dyskinesia does in fact emerge while patients continue at the same dose, a fact strongly suggesting that some other process, in addition perhaps to a progressive up-regulation, is at work. This last theory is of some interest given the evidence, noted below, for the treatment efficacy of vitamin E, an antioxidant. When tardive dyskinesia does first appear, a decision must be made as to whether ongoing treatment with a neuroleptic is required, carefully weighing the risk of worsening dyskinesia against the risk of relapse. In the case of schizophrenia, the balance often tips towards continuing neuroleptic treatment. If treatment is continued, efforts, if not already in place, should be made to keep the dose as low as possible, consistent with adequate symptomatic control. In cases due to treatment with a first-generation antipsychotic, consideration should be given to switching to a second-generation agent; with such a switch, adequate symptom control is maintained or improved and the risk of worsening tardive dyskinesia with further treatment is lessened. In cases in which treatment cannot be discontinued, or in cases in which discontinuation is possible but symptoms fail to go into remission, various medical treatments may be considered, including vitamin E, vitamin B6, melatonin, branched chain amino acids, piracetam, and dopamine depletors, such as tetrabenazine, alpha-methyldopa or reserpine. The overall differential diagnoses of chorea, dystonia, akathisia, and tics are discussed in Sections 3. Schizophrenia may at times be characterized by choreiform movements, as pointed out by Kraepelin in the early part of the twentieth century (Kraepelin 1971) and confirmed by subsequent investigators (Farran-Ridge 1926; Mettler and Crandall 1959; Owens et al. Both dystonia and akathisia may occur as acute extrapyramidal side-effects of antipsychotics but are readily distinguished from tardive dystonia or tardive akathisia by their p 22. From a pharmacologic viewpoint branched chain amino acids constitute an interesting option (Richardson et al. Administration of a combination of valine, isoleucine, and leucine (given in a ratio of 3:3:4 at a dose of 222 mg/kg three times daily) is followed by a fall in the plasma levels of the aromatic amino acids tyrosine and tryptophan, with presumably a fall in central nervous system levels of dopamine and serotonin, and it is this change that presumably accounts for the improvement in the tardive dyskinesia. Piracetam (not available in the United States), in a dose of 4800 mg/day, was recently found to be effective (Libov et al. Of these options, the vitamins and melatonin are the most benign, and one of these should probably be tried first; vitamin E has by far the most support and is a reasonable starting point. In some cases combination treatment with two or more of these agents may be appropriate.

Similar strategy has been attempted in larger species such as dogs for the treatment of ceroid lipofuscinosis (Biferi et al. In those cases, it is assumed that the ependymal and choroid plexus cells act as therapeutic reservoirs for the secretion of soluble enzymes or neurotrophic factors throughout the cerebral tissue. Whether or not long-term gene expression can be achieved remains unknown, especially because of the relatively fast turnover rate of the ependymal cells (Chauhan and Lewis, 1979). Additionally, the insertion of a catheter through the lower section of the spinal cord can eventually be advanced rostrally to the cisterna magna with limited risks. Whether or not placing the subject in the Trendelenburg position right after infusion can potentiate the efficacy of brain transduction by this procedure remains debated (Meyer et al. Unfortunately, scaling up the dose of vector to treat larger animals has proven challenging, the spread of the vector remaining limited and localized in the lumbar segment of the spinal cord. This finding served as the basis of many preclinical and clinical programs described in more detail below. Interestingly, notwithstanding some discrepancies between the reported studies, the transduction profile in the brain in animals has been reported to shift accordingly to the age of treatment: while Neuron 101, March 6, 2019 847 Neuron Review tently targeted regardless of the age of the subject. In summary, the choice of the route of administration is a critical one yet requires a balancing of multiple parameters along a risk-benefit equation. Historically, local routes of injection have been preferred as they minimize the safety considerations while maximizing delivery. Driven by the desire to overcome the invasiveness of the local administration procedure and/or the clinical need to target more broadly than what a local injection route can deliver, novel technologies were, and often still are, needed that enable meaningful levels of gene transfer via these routes. In certain cases, various routes of administration are combined when either technologies are too limiting or the disease presentation. Observations included elevated transaminases, degeneration of dorsal root ganglia, impaired ambulation, proprioceptive deficits, and ataxia (Hinderer et al. Moreover, host responses can be unpredictable and dependent on disease state, route and compartment of administration, genetic predispositions, or other idiosyncratic variables. Host Response Immunological responses to a gene therapy can significantly impact the safety and longevity of any gene therapy. During these treatments, some patients develop antibody responses to the injected enzyme. Brain, spinal cord, eye, and cochlea have limited access to circulating antibodies or infiltrating immune cells and, in certain cases, mechanisms to actively dampen immune response (Forrester et al. Similarly, in the eye, programs using a subretinal route of injection have overall safely progressed in the clinical studies, presumably due to the local immune privilege of the retina, the small dose, and the containment of the vector in the subretinal bleb (Trapani and Auricchio, 2018). Nonetheless, immune privilege is a relative concept, as in higher animal studies inflammatory responses have been noted particularly when higher doses are administered, possibly due to innate immune sensing in the retina or leakage of virus into the vitreous due to the subretinal injection procedure (Khabou et al. Direct intravitreal, which conceptually has noted advantages over subretinal injection, illustrates the limits of immune privilege even more. These responses remain poorly understood, mainly because they are only evident in larger animal models and human studies (Cukras et al. Ectopic expression of the transgene product can be a source of antigenicity or toxicity, an issue that warrants the development of strategies to restrict expression of the therapeutic protein to targeted tissues. Capsid modifications can be made to reduce liver targeting and promote transduction of the neural tissue (Castle et al. While these strategies have overall proven to be adequate in the ongoing clinical studies, it is clear they do not provide a solution for many of the outstanding concerns in the field. These and other questions remain the topic of investigation and technology development in the laboratory (reviewed in Mingozzi and High, 2013). Indeed, since no mechanism actively duplicates the transgene during mitosis, its expression is eventually lost in a dividing cell population. The risk for generating insertional mutagenesis therefore does exist and was recently reviewed in detail (Chandler et al. While those findings have recently been reproduced in a large study using various different serotypes and longer time points (up to 24 months) (Chandler et al. Additionally, a detailed genomic analysis demonstrated that the vector integration sites were mapped in Mir341 (within the Rian locus), which only exists in rodents (Chandler et al. In the specific case of gene transfer applied to neurological disorders, insertional mutagenesis may only be a concern when high doses of vector are injected systemically. Clinical Progress: Illustrative Case Studies Clinical gene therapy has come a long way to overcome perceived and real concerns about safety and its potential to markedly intervene in disease in humans, and today the demonstrated proof of concept of the clinical utility of gene therapy is clear. For an in-depth overview of the progress and clinical studies in the field of ophthalmology, specifically for inherited retinal disorders, we refer to a number of recent reviews on the subject (DiCarlo et al.