"Order viagra capsules visa, erectile dysfunction over 50".

S. Musan, M.B. B.CH. B.A.O., M.B.B.Ch., Ph.D.

Vice Chair, Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine

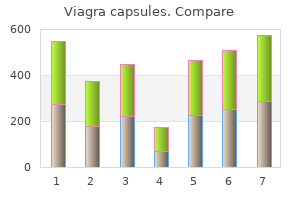

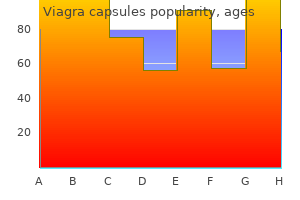

Six patterns of blood supply to the fasciocutaneous plexus: A, direct cutaneous vessel; B, direct septocutaneous vessel; C, direct cutaneous branch of muscular vessel; D, perforating cutaneous branch of muscular vessel; E, septocutaneous perforator; F, musculocutaneous perforator. Computer images of angiograms performed on 28 segmental arteries of the body were analyzed according to the tissue layer in which they were dominant (whether dermal, superficial, or deep adipofascial layers), their axiality, and their size. After perforating the deep fascia, the arteries were assigned to one of six different types (Fig 5). The arteries were localized on a whole body map and the relationship between the type of artery and the mobility of the tissue it supplied was considered. A large vena communicans (C) connects these systems, and the alternative pathways of four venae comitantes are shown. Below, Other regions where the predominant venous drainage is by means of the venae comitantes. Taylor and colleagues37 studied the venous territories (venosomes) of the body and showed that the cutaneous venous plexus is composed of valvular superficial and deep cutaneous veins that parallel the course of adjacent arteries, and of oscillating avalvular veins that permit bidirectional flow between adjacent venous territories (Fig 7). Zhong and coworkers38 classified the venous architecture of the skin and subcutaneous tissue into four superimposed layers that are drained by two large venous trunks, a superficial and a deep (Fig 8). The superficial venous trunks are located in the subcutaneous tissue and do not accompany arteries. The authors propose that the main venous drainage of an anatomic region can be primarily via the deep venous trunk, the superficial venous trunk, or both. Small epidermal and dermal branches were collected into a superficial polygonal venous network located in the deep dermis or superficial adipofacial layer. Osteal valves were identified at the anatomosis of the first draining dermal branches and the polygonal venous network to resist reflux. The authors distinguish between a superficial vein that is located above the deep fascia and a cutaneous vein that is superficial and does not accompany an artery. They are an important bypass to the unidirectional valves of the cutaneous veins and permit retrograde flow in distally based flaps. Multiple venous anastomotic connections adequately drain most dermal regions via either the cutaneous vein or the venae comitantes of the source artery. Classification schemes have historically been very confusing because they were based on an incomplete understanding of flap vascularity. As our knowledge of the vascular anatomy of skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle increased, new flap types were developed and classifications were proposed that were frequently incongruent with previous systems and with one another. When distant pedicled flaps became commonplace,3 they were labeled as local or distant depending on their proximity to the donor Fig 9. Subsequently flaps were categorized by their tissue composition: muscle, skin, musculocutaneous, fasciocutaneous, septocutanous, and compound flaps. This classification system can be confusing because different flaps based on different blood supplies but of the same composition can be harvested from the same region. The intrinsic blood supply of a flap is the most critical determinant of successful transfer and is therefore the most clinically valid method of classification. Numerous anatomic studies of the blood supply to the skin and fascia have contributed to our understanding and led to a simpler classification of cutaneous flaps. For example, the fasciocutaneous flap that was originally defined by the presence of deep fascia is now classified according to the pattern of cutaneous vascularity through the fasciocutanous plexus, and frequently does not include fascia. A fasciocutaneous flap can be any flap based on the fasciocutaneous plexus and composed of any or all of the component layers between the skin and deep fascia. Daniel and Kerrigan29 grouped flaps into three categories according to their method of movement, composition, and vascularity. In our discussion of specific flaps we have combined the latter two criteria because they overlap with older terminology based on composition terminology. Method of Movement Skin flaps can be grouped according to the technique used to transfer the tissue and the distance between the donor and recipient sites.

A high index of suspicion for lymphoma as a cause of common complaints in the head and neck region can lead to early diagnosis and improved outcome. Beyond the role of diagnostician, the head and neck surgeon will often be the one who obtains tissue for diagnosis. The age distribution is bimodal with a peak in the low 20s and a second peak in the low 40s. It arises almost exclusively in nodal tissue; it manifests as enlarged rubbery painless nodes in the low neck and/or supraclavicular fossa, or above the hyoid in the submental, 5. Night sweats: Drenching sweats that require change of should be classified as bedclothes either A or B according 3. Weight loss: Unexplained weight loss 10% of the to the absence or usual body weight in the 6 months before diagnosis presence of defined constitutional symptoms. Pruritus as a systemic symptom remains controversial and is not considered a B symptom. A history relating to lymphadenopathy or extranodal disease involvement, such as unilateral tonsillar hypertrophy or nasal obstruction, is a concern. Imaging Knowledge of the anatomic extent of disease is required for treatment planning. Bone marrow involvement occurs in 5% of patients; biopsy is indicated in the presence of constitutional B symptoms or anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia. These patients are candidates for chemotherapy, combined modality therapy, or radiotherapy alone. At the onset of symptoms or complications, a single-agent oral alkylator therapy may induce and maintain clinical remission. For bulkier or clinically staged localized disease, chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment. An intensive but abbreviated chemotherapy course followed by consolidation radiotherapy has, until recently, been the treatment of choice. Disseminated aggressive disease is best treated with full-intensity, full-course chemotherapy. Occasionally, palatine, lingual or nasopharyngeal tonsil tissue is excised and submitted. Where possible, care should be taken to provide intact samples large enough to provide meaningful nodal architecture information on which to base pathologic diagnosis. All permanent specimens should be submitted dry or in saline but not in formalin to allow immunohistochemical and flow cytometric studies to complement traditional pathology. Lymphocyte-predominant disease has an excellent prognosis; the prognosis of the nodular sclerosis variant is also very good. The most worrisome of these complications are secondary malignancies, which occur with an overall incidence of 5%. Complications of radiotherapy include those specific to head and neck irradiation, such as xerostomia and mucositis, as well as generalized fatigue and weight loss. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the midface region is one of the rarest forms of extranodal lymphoma representing 0. The incidence of these tumors is substantially higher among Asian and South and Central American populations. N Epidemiology Idiopathic midline destructive disease affects a wide age range, peaking in the sixth decade. Males are predominately affected, and the disease is much more common in persons resident in East Asia. N Clinical Signs and Symptoms Initial symptoms are usually those of a nonspecific rhinitis or sinusitis with nasal obstruction and nasal discharge. As the disease progresses, ulcerations spread, destroying the soft tissues, cartilage and bone. Death after a long duration may be the result of cachexia, hemorrhage, meningitis, or intercurrent infection.

A newer alternative is a chemical sphincterotomy using an injection of botulinum toxin (Botox) into the internal sphincter. The abscess may form a track like a horse shoe behind the rectum to the opposite ischiorectal fossa. It is stinging in nature and lasts for a while after the passage of stool, sometimes 2 or more hours later. There is often slight bleeding and, because of the pain, the patient is usually constipated. It may be impossible to do a rectal examination without anaesthetic; the fissure may then be palpable as a crack in the anal canal. Treatment Early surgical drainage to prevent rupture and the possible formation of a fistula in ano. Aetiology the term fistula in ano is loosely applied to both fistulae and sinuses in relation to the anal canal. The great majority result from an initial abscess forming in one of the anal glands that pass from the submucosa of the anal canal to open within its lumen. Growth of bowel organisms, as opposed to skin flora, from an anorectal abscess is suggestive of the presence of a fistula. Superficial Low anal Superficial fistulae may be either subcutaneous or submucous, and are superficial tracks resulting from rupture, respectively, of subcutaneous and submucous abscesses. Intersphincteric and transsphincteric fistulae are examples of low anal fistulae, in which the track is below the anorectal ring; they constitute 95% of all fistulas. They differ in their penetration through the external sphincter, and most are at a low level with the track passing through the subcutaneous part of the sphincter. Suprasphincteric fistulae pass via the intersphincteric space to open into the anus above the puborectalis and are high anal fistulae. Anorectal fistulae, fortunately rare, extend through levator ani to open above the anorectal junction. Clinical features There is usually a story of an initial anorectal abscess, which discharges. Following this, there are recurrent episodes of perianal infection with persistent discharge of pus. Accurate assessment of the extent of the fistula track, in particular its relation to the anal sphincter, is crucial. Laying open of the whole track of a suprasphincteric fistula in error will completely divide the sphincters and result in incontinence. Treatment Superficial and low-level anal fistulae are laid open and allowed to heal by granulation. Because no sphincter, or only the subcutaneous part of the external and internal sphincters, is divided in this procedure, there is no loss of anal continence. Fistulae can only be treated in this manner when they quite definitely lie below the level of the anorectal ring; careful assessment is therefore important. If either of these sphincter-preserving treatments fails, the lower part of the track is laid open and a non-absorbable strong ligature. Treatment Depends on the underlying pathology and may call for repeated dilatation, plastic reconstruction, defunctioning colostomy or, in the case of malignant disease, excision of the rectum. The rectum and anal canal 225 Prolapse of the rectum this may be partial or complete. Palpation of the prolapse between the finger and thumb reveals that there is no muscular wall within it. It may occur in infants who, unlike the usual textbook description, are not wasted but often perfectly healthy. Treatment of these babies requires nothing more than reassurance of the parents that the condition is self-curing. In adults, it usually accompanies prolapsing piles or sphincter incompetence, and may present with pruritus ani. Apart from the discomfort of the prolapse, there is associated incontinence owing to the stretching of the sphincter and mucus discharge from the prolapsed mucosal surface. An alternative is the Altemeier5 perineal rectosigmoidectomy, in which a full thickness resection of prolapsing rectum is performed. Pruritus ani There are four principal causes of pruritus ani: 1 Local causes within the anus or rectum.

With exposure to higher concentrations, damage to the trachea and lower airways may occur, producing laryngitis, cough, and dyspnea. With large exposures, necrosis of the airway mucosa occurs leading to pseudomembrane formation and airway obstruction. Secondary infection may occur due to bacterial invasion of denuded respiratory mucosa. Exposure to higher concentrations produces progressively more severe conjunctivitis, photophobia, blepharospasm pain, and corneal damage. Intensive care similar to that given to severe burn patients is required for pts with severe exposure. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary for laryngeal spasm and severe lower airway damage. Pseudomembranes should be removed by suctioning; bronchodilators are of benefit for bronchospasm. The use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and/or stem cell transplantation may be effective for severe bone marrow suppression. Mechanism Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase accounts for the major lifethreatening effects of these agents. At the cholinergic synapse, the enzyme acetylcholinesterase functions as a "turn off" switch to regulate cholinergic synaptic transmission. Inhibition of this enzyme allows released acetylcholine to accumulate, resulting in end-organ overstimulation and leading to what is clinically referred to as cholinergic crisis. Clinical Features the clinical manifestations of nerve agent exposure are identical for vapor and liquid exposure routes. Initial manifestations include miosis, blurred vision, headache, and copious oropharyngeal secretions. Once the agent enters the bloodstream (usually via inhalation of vapors) manifestations of cholinergic overload include nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, muscle twitching, difficulty breathing, cardiovascular instability, loss of consciousness, seizures, and central apnea. Liquid exposure to nerve agents results in differences in speed of onset and order of symptoms. Contact of a nerve agent with intact skin produces localized sweating followed by localized muscle fasciculations. Once in the muscle, the agent enters the circulation and causes the symptoms described above. Nerve Agents Since nerve agents have a short circulating half-life, improvement should be rapid if exposure is terminated and supportive care and appropriate antidotes are given. Thus, the treatment of acute nerve agent poisoning involves decontamination, respiratory support, antidotes. Decontamination: Procedures are the same as those described above for sulfur mustard. Respiratory support: Death from nerve agent exposure is usually due to respiratory failure. Atropine: Generally the preferred anticholinergic agent of choice for treating acute nerve agent poisoning. Thus, atropine can rapidly treat the life-threatening respiratory effects of nerve agents but will probably not help neuromuscular effects. In the mildly affected pt with miosis and no systemic symptoms, atropine or homoatropine eye drops may suffice. Oxime therapy: Oximes are nucleophiles that help restore normal enzyme function by reactivating the cholinesterase whose active site has been occupied and bound by the nerve agent. Anticonvulsant: Seizures caused by nerve agents do not respond to the usual anticonvulsants such as phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, valproate, and lamotrigine.