"Order aldactone 100 mg on-line, blood pressure medication hair loss".

N. Candela, M.A., Ph.D.

Clinical Director, University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine

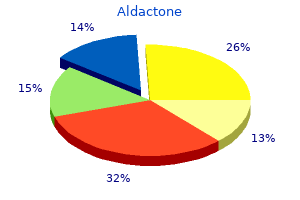

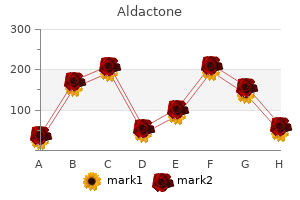

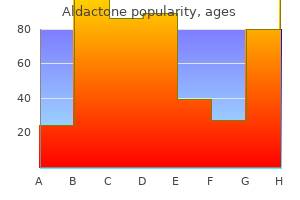

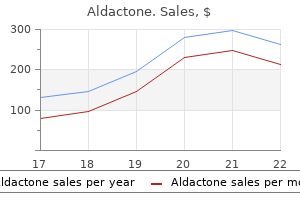

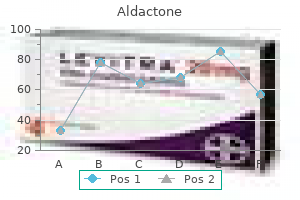

Different types of benefits and costs of animal brucellosis mass vaccination in Mongolia are seen in Figure 14 below. Brucella spp may undergo L-transformation when exposed to certain antibiotics, resulting in a cell wall deficient form [81]. The effect in preventing serological detection and resultant creation of carrier animals is not clear. However, it has been demonstrated that long and complex treatments can successfully eliminate shedding of organisms from long-term carriers in cattle [82] and small ruminants [83], but it is believed to be economically unviable. In general, antibiotic therapy in pigs has been effective in limiting the bacteremic stage of the disease, but after therapy was discontinued, viable B. In carefully selected circumstances it would probably be possible to suppress multiplication of B. Preliminary results indicate that they are not effective during the abortion stage; they did not prevent abortion (presumed the foetus were already colonised at the time of treatment) but further analysis is ongoing. Prophylaxis (Prevention) Biosecurity measures to ensure the disease does not enter the herd are useful but might be very difficult to implement in the settings that characterise the developing world. New animals entering the herd, as well as semen, should come from Brucella negative herds/farms. Animals entering the herd should be quarantined and tested, before they are allowed to mix with the remaining animals. The different types of vaccines, their advantages and disadvantages, are discussed in Section 6. Livestock vaccines currently available are effective in reducing production losses and reducing transmission, but do not prevent the animals getting infected, or seroconverting after exposure to virulent strains. Options and strategies for control programs at national, sub-national or regional level: Control of brucellosis is a long term program that should be adapted to the local circumstances. The most successful efforts to control and in many cases eradicate brucellosis have been in high and middle income countries (and one low income country, Nigeria). The general pattern has been to establish a diagnostic and surveillance system and estimate the prevalence and distribution of brucellosis. Based on the prevalence results, different strategies might be applied (see Figure 15 below). Initial control measures, including vaccination, may be implemented to reduce an initial high prevalence. From there, testing, quarantine and slaughter with compensation policies are established. Often, the final stages are the most difficult, when prevalence rates are low and the cost of finding the final positive animals is very high. Are animals individually identified to ensure seropositive animals are correctly identified Attempts to control and eradicate brucellosis in middle-income countries using the classical approaches have been much less successful. These include the attempts in Mongolia which progressed at a very slow pace, as well as less than successful control programs in Egypt, Israel (B. In low and middle income countries, more targeted control measures may be more realistic. Under conditions of high to moderate prevalence, inadequate veterinary resources, inability to control livestock movement, widespread brucellosis in feral animals or wildlife, livestock owners unaware of the importance of the programme or not strongly committed to public disease control, or limited diagnostic capabilities, targeted mass vaccination of all animals (including adults) might be the optimal tool for reducing level of infection. Reduction of prevalence through targeted and time-bound vaccination campaigns may be economically beneficial as it could stop the spread of an outbreak of B. The strategy chosen will depend of the country resources, the epidemiological situation, the political will, the legal framework (for example legislation required for test, slaughter and compensation), veterinary services and laboratory infrastructure, animal movement control, animal/herd identification practices and availability of good quality vaccines. In the considerations for vaccination, it is stated that an effective vaccination requires coverage of over 80% of the eligible animal population, and vaccination carried out for a period greater than twice the average production life (over 10 years in sheep and goats). As for considerations of the different scenarios in the Greater Horn of Africa, they define high-prevalence, endemic situation in small ruminants, when there is over 5% herd prevalence and in those cases mass vaccination is recommended. Where risk factors cannot be controlled (for example, under conditions of transhumance), vaccination is recommended even when the prevalence is lower.

Storage and archives Collections of well characterised specimens including infectious agents, infected tissues and fluids, as well as negative control tissues and fluids, are critical for future research and development efforts, for retrospective studies, epidemiological investigations, and for providing critical reference materials used in assay standardisation, validation, and proficiency testing programmes. Materials routinely needed as reference standards and for assay validation are described in Chapter 1. The materials maintained in laboratory archives should be representative of the agents handled and the types of samples used in the different testing methods performed, which would variously include fresh and fixed tissues and fluids, paraffin-embedded tissues, and stabilised or otherwise preserved cultures. The principle components of any laboratory archive include the appropriate means of stabilisation and storage, a complete system of documentation and inventory of the material stored, and implementation of biosafety and laboratory biosecurity measures needed to manage the collection. Samples stored for periodic access such as assay reference materials should be aliquotted to avoid potential problems associated with repeated retrieval and return to storage. They may be stored separately from specimens or samples stored for historical, long-term preservation. Storage conditions should be managed to maintain viability, biochemical, and immunological properties of the samples to the maximum extent possible. Considerations for preserving the integrity of the samples must include protection from desiccation. Unique or valuable isolates and materials should be stabilised and stored using at least two different procedures and storage locations. Ultralow freezing may not be a practical choice as it is expensive to maintain, but cost must be balanced with the fact that biological degradation of the sample over time is an increasing risk at warmer freezer temperatures. Reference materials that are to be accessed with any regularity should be stored in appropriately-sized aliquots to allow access while minimising the number of times the "master stock" is handled. Repeated freezing and thawing of samples should be avoided as it can denature antigens, result in loss of viability of fastidious agents, and can precipitate the over-growth of contaminants or unwanted microorganisms in the sample. Methods for stabilisation and storage of samples at room temperature range from commercially available technologies that largely target nucleic acid stabilisation, lyophilisation processes, to the relatively low-tech versions of drying fluids on filter paper disks or storage of biological samples in the presence of desiccating agents such as silica gel or grains of rice to absorb moisture. Considerations such as speed at which a sample is frozen or chemically preserved, size and density of the material to be preserved, storage container and media, and also protocols for reconstitution, thawing, and reviving agents will vary with different tissues and agents. Whether the plan is to store samples frozen or at ambient temperature, for most tissues and groups of infectious agents there are specific preservatives, stabilisation protocols, and storage conditions that are considered optimal; the current published literature should be consulted. The unique identity of the tissue, fluid, or agent and the storage location are best maintained in an electronic or paper inventory record which also documents the date the material was obtained, date and method of preservation, volume of material stored, source of the material including associated species, geographical location, and the clinical history of the donor animal and the disease situation of the flock or herd. Additional information is extremely useful and generally includes the original method of isolation/recovery, characterisation. Inventories are most often organised by assigning a unique identifying number or alphanumeric code to each sample (sample container) that is cross-referenced to a database or inventory log. Inventory records can be manual data logs, computerised spreadsheets, or specialised computer programs. However the records are managed, they must be kept current and the information entered must be traceable to its source. The identification of the individual making an entry or modification to the sample inventory should be recorded. The laboratory should consider all biorisk management measures needed to protect the integrity of the sample, as well as the health of the workers and environment, from the time the original sample is received through the long-term storage and ultimate use or destruction of the material(s). The appropriate level of laboratory biosecurity, including controlled access to the archived samples and inventory records, is an important consideration for laboratories maintaining biological inventories and archives. The laboratory should also have a back-up plan for the transfer or destruction of potentially dangerous archived materials in the event of power failures or other compromises to the storage environment. National and international regulations and legislation, including requirements for permits and licenses to receive, maintain, work with, and distribute specific agents and tissues must be followed for all laboratory archives. Current regulatory information in regards to receiving and storage of biological materials can be found on the European Biological Resource Centre Network website ( Saphenous vein puncture for blood sampling of the mouse, rat, hamster, gerbil, guinea pig, ferret and mink. Sample size calculation for each of the main purposes of testing, where random sampling has been used, may be approached as follows: 1. Demonstrate freedom from infection in a defined population compartment/herd where the prevalence is apparently zero) (country/zone/ Frequently, the objective of sampling is to determine if a disease is present or absent in a population at a specific threshold (design prevalence).

Preventing the entry of these pathogens into Europe is not possible as they are carried over long distances by asymptomatic wild (aquatic) birds, both during migration and through trade (legal and illicit). True swine influenza in humans: recent different findings in the United States and Europe (Germany) [website]. Rapid risk assessment: Potential resurgence of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza. Over 76% of cases occurred in the seven countries reporting 3000 cases or more each (France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Romania, Spain and the United Kingdom). This gender imbalance was largely restricted to those aged 25 years and older and was observed in every country except Iceland. In Estonia, Greece and Lithuania this imbalance was very pronounced,withmale-to-femaleratiosofupto2. Cases older than 64 years (18% overall) were particularly frequent in the Czech Republic, Finland and Slovenia (>30%). No country showed any consistent change in the five-year trend in paediatric rates. Country-specific 10-year trends for this ratio were mostly inconclusive, butclearlyincreasinginBulgaria,ItalyandSweden,and decreasing in Denmark. Due to differences in testing policies and data collection, the completeness of data varied. Attheotherend of the scale, the proportion of co-infected cases ranged between 0% and 6. AggregatednationaldatawerereportedfromFranceand Italy, while Spain reported aggregated data with partial coverage. However, in 12 Member States, cases of foreign origin accounted for the majority of cases, reaching 85. From 2001 to 2010, most Member States observed a decrease in cases of national origin, with the exception of Spain, which saw an increase due to a substantial decrease in cases of unknown origin. Eleven Member States experienced rising trends of cases of foreign origin, while ten Member States reported stable trends. Only Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Luxembourg and Slovenia registered a decline in cases of foreign origin between 2001 and 2010. Withvaluesunder60%,Cyprus,Denmark, Estonia and Hungary reported the lowest proportions of cases with successful treatment. Country-specific five-year trends increased in seven Member States, decreasedineight,andwereinconclusiveintheremainder. Although the quality and comparability of reported data has improved considerably in recent years, the reader should be careful when making direct comparisons across countries. Despite recent progress, Romania, Bulgaria and the Baltic countries still have reported rates several times higher than those in the low-incidence countries. Consistently increasing fiveyear trends are seen only in Cyprus and Sweden, where they appear to be mainly driven by cases of foreign origin (born outside of the reporting country), although total reported rates in both countries remain well under 10per100000. In order to achieve optimal detection of infectious cases as well as early identification of drug-resistant cases, a higher proportion of cases need to be bacteriologically confirmed. Member States should evaluate the extent to which the underachievement in culture-confirmation targets reflects sub-optimal practice in testing by culture, or in the reporting of bacteriological results. The true incidence of chlamydia is likely to be higher as this infection is liable to underreporting or asymptomatic disease. The notification rate among those between 15 and 24 years of age is 821 per 100000 population; young women are affected more often than young men. However, this has to be interpreted with caution as it most likely reflects changes in screening and testing practices in a number of countries.

Recent investigations suggest that the vomiting-type toxin can be detected through animal models (cats, monkeys) or, possibly, by cell culture. Other Resources Loci index for genome Bacillus cereus GenBank Taxonomy database "Produce Handling and Processing Practices" (1997) Emerging Infectious Diseases 3(4). Organism Streptococcus A is not a major cause of foodborne illness, although serious complications occasionally develop if foodborne illness does occur. Streptococci can be found on the skin; the mucous membranes of the mouth, respiratory, alimentary, and genitourinary tracts of human and animals; and in some plants, soil, and bodies of dirty water. Optimum incubation temperature is usually 37oC, with relatively wide variations among species. The genus is defined by a combination of antigenic, hemolytic, and physiologic characteristics that are further refined into Groups A, B, C, D, E, F, G, N, etc. This chapter will focus on Group A, since most group D species have been reclassified as enterococci and are covered in a separate chapter. Some people infected with foodborne Streptococcus have no symptoms, but those who do will start to have them in about 1 to 3 days after eating contaminated food. They may start with red, sore throat (with or without white patches), painful swallowing, high fever, nausea, vomiting, headache, discomfort, and runny nose. However, 2 or 3 weeks afterwards, some people develop scarlet fever, which includes a rash, or rheumatic fever, which can harm the heart and other parts of the body, or Streptococcus could spread to other organs and cause serious illness or death. Children 5 to 15 years old and people with weak immune systems are more likely than others to develop the serious forms of the illness. Infected food handlers are thought to be the main way food is contaminated with Streptococcus. In most cases, the food was left at room temperature for too long, letting the bacteria multiply to harmful levels. Disease Mortality: In otherwise healthy people, most cases of foodborne Streptococcus infection are relatively mild. In patients who develop invasive disease (most likely to occur in people with underlying health issues, such as those who are immunocompromised), the death rate is estimated at 13%. Infective dose: the infectious dose for group A Streptococcus probably is fewer than 1,000 organisms. If rheumatic fever or scarlet fever develop, they usually do so 2 to 3 weeks after the initial infection. Disease / complications: Some foodborne Streptococcus Group A infections are asymptomatic. Of those that are symptomatic, most manifest as pharyngitis (and are commonly referred to as "Strep throat"). However, the infection may also result in complications, such as tonsillitis, scarlet fever, rheumatic fever, and septicemic infections. Symptoms: Sore, inflamed throat, on which white patches may or may not appear; pain on swallowing; high fever; headache; nausea; vomiting; malaise; and rhinorrhea. In cases of scarlet fever, a rash may develop, which begins on the sides of the chest and abdomen and may spread. Symptoms of rheumatic fever, which affects collagen and causes inflammation, appear in the heart, joints, skin, and/or brain. Duration of symptoms: Symptoms of uncomplicated illness generally begin to resolve within about 4 days. Antimicrobials, such as penicillin (or ceftriaxone), azithromycin, and clindamycin, are used to treat Group A Streptococcus disease. Other alternatives for prevention and control of the disease that are being considered include vaccines and phage and immunologic therapies. Route of entry: Oral (although the organism also may be spread through vehicles other than food and causes other types of serious illness that are not addressed in this chapter). The mechanisms and functionality of these virulence factors are extremely complicated and not very well defined. Sources Food handlers are thought to be a major source of food contamination with Streptococcus Group A.