"Generic 1pack slip inn otc, herbals that cause insomnia".

X. Kan, M.A., M.D.

Program Director, Kansas City University of Medicine and Biosciences College of Osteopathic Medicine

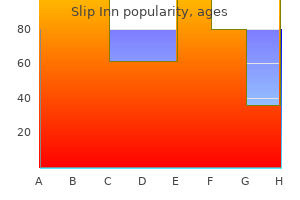

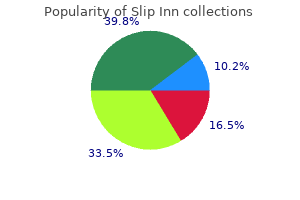

The campaign, which began in 1997, presented these negative outcomes as certain, as opposed to probable, consequences of smoking. Six of the seven advertisements produced since 1997 graphically portray health damage to evoke a strong visceral response of disgust in the viewer. Two advertisements depicting smoking as causing incremental damage leading to blindness in one case and chronic lung disease in another were added in the fourth year of the campaign. Call showed a smoker picking up a telephone, calling a quitline, and a counselor responding to the call. California-Changing Social Norms about Smoking the California Tobacco Control Program, funded in 1989 by Proposition 99, was the first ongoing, comprehensive statewide tobacco control program in the United States. The California media campaign is seen as an essential component of the statewide tobacco control program, lending support to local tobacco control interventions. The media campaign is designed to frame the issues and attract and sustain public attention. Television advertisements created for this campaign portray industry executives as unconcerned in response to information about the negative health effects of cigarettes. Other advertisements use youth actors to convey the notion that cigarettes are addictive. Launched in 2000 with more than $100 million per year for media, the Legacy "truth" campaign was a national landmark event in the history of tobacco counteradvertising. The "Body Bags" series began with an advertisement showing young people jumping out of a truck and piling body bags on the sidewalk outside of what was labeled a "major tobacco company. Shifting to a testimonial approach, a later series ("Follow the Dots") featured young people speaking in emotional segments about loved ones they have lost purportedly because of smoking. The campaign designers rejected the heavy "life or death" tone of other antitobacco campaigns. They claimed that social marketing approaches used in other states were having little impact, and the campaign needed to provide a brand that would give youth a way to identify themselves. O v e r v i e w o f M e d i a I n t e r v e n t i o n s i n To b a c c o C o n t r o l Virginia-Making Smoking Look "Stupid" In 2002, Virginia launched a youth-focused campaign designed to empower the youth of the state to "choose not to use tobacco products. Another series showed young actors engaged in gross or dangerous behavior, such as licking garbage cans or climbing a pole in a thunderstorm, the stupidity of which was equated with smoking. Pharmaceutical advertisements on television may be designed to encourage uptake of pharmaceutical smoking cessation products among adult smokers who are ready to quit. They concluded that among adult smokers who are not ready to quit, implying that these products offer an "escape from danger" may lead smokers to defer quit attempts and lower their perceptions of smoking risks. These advertisements tended to describe the benefits of one medication in contrast to another and suggested that the product can be a great help in achieving cessation. Unlike most government-sponsored advertisements, these advertisements have so far narrowly targeted smokers who are ready to take action to quit smoking. The Role of the Media documentary evidence and consequent growing liability that tobacco companies marketed their products to youth and misled consumers and the general public about the health risks of tobacco use. All of the adolescents interviewed were nonsmokers who responded that they did not need to smoke to be cool. Later executions showed young actors involved in popular activities such as karate and skateboarding, demonstrating that they were better off for not smoking. In July 1999, Philip Morris launched a campaign emphasizing parental responsibility for talking to children about smoking, with the slogan, "Talk. A first step toward answering these questions is to examine some useful parameters on which advertisements can differ. The marketing literature conceptualizes the characteristics of advertisements in terms of the message strategy.

This volume offers important lessons in how the media could be harnessed to further reduce tobacco use in the United States, and these lessons have implications for other nations seeking to achieve the same aim. Despite this extensive body of work, a considerable amount of research remains to be done, partly because the relationship between tobacco promotion and tobacco control is dynamic: Action in one area produces change in another. As long as tobacco companies are able to develop new tobacco marketing strategies to circumvent tobacco control measures, the need for monitoring, research, and policy advisement continues. More broadly, the need for research continues as the communications environment becomes ever more complex. A growing range of communication 598 channels and information-delivery systems provides increasing opportunities for tobacco companies to target communications to consumers, sometimes with little oversight from policymakers, regulators, or those working in tobacco control. The fragmentation of audiences across this proliferation of channels also means that those working to stem tobacco use must consider a bewildering number and variety of communication channels to run campaigns and deliver antitobacco messages. Limited funds and resources are further strained, and efforts to monitor tobacco promotion become more complex. The growing socioeconomic disparity in tobacco use is another important trend with implications for study of tobacco-related media communications. In general, tobacco users are more likely to be among the groups that are disproportionately deprived in social and economic areas. A more vigorous, systematic, and empirical research agenda can further understanding of how mass communications contribute to tobacco promotion and tobacco control. Against this background, this final chapter discusses future directions for such media and communications research. Future Directions to Address Tobacco Promotion A major conclusion of this volume is that cigarettes are one of the most heavily promoted products in the United States. The information on tobacco marketing in the chapters of this volume plainly demonstrates the evolution of these practices in response to imposed tobacco marketing restrictions. In general, there is abundant evidence that tobacco companies failed to adhere to voluntary agreements on tobacco marketing (see chapter 3). However, once one avenue for tobacco marketing is closed by an imposed restriction, the attention of the tobacco companies shifts to alternative media to generate exposure to tobacco brands. For this reason, partial restrictions on tobacco marketing have limited effectiveness in reducing tobacco use and consumption (see chapter 7). Because restrictions were imposed on tobacco marketing through television, radio, and billboard advertising, alternative avenues for tobacco marketing have emerged in the United States. Second, cigarette packaging has assumed a more significant role in communicating the brand image of tobacco products (see chapter 4). Third, sponsorship of events by tobacco companies, to promote both tobacco brands and corporate image, has increased substantially (see chapters 4 and 6). Depiction of smoking in movies, including use of cigarette brands, has also become more prevalent and is a risk factor for youth smoking (see chapter 10). Research has provided convincing evidence that the tobacco industry has modified marketing strategies in step with the extent of tobacco control. As detailed in chapters 4 and 7, research demonstrates that the placement of tobacco in convenience stores beside candy and everyday consumer goods increases the sense of "friendly familiarity" with tobacco, increases youth perceptions of high smoking prevalence, and may increase the likelihood that youth will initiate smoking. Research is needed to increase understanding of the ways in which these price discounts interact with other promotional strategies to influence tobacco 15. Studies of cigarette sales data might analyze sales volume data from convenience store or supermarket scanners. Only one relatively small-scale study of cigarette sales data at the retail level has been performed. Cigarette packaging is all the more important because, unlike other consumer-product packaging that is discarded after purchase, cigarette packs are taken out and may be displayed whenever a cigarette is smoked. Research on perceptions about popular cigarettes, including those that appear to communicate reduced harm, could provide helpful information on youth perceptions and misperceptions of particular brands. Youth-oriented education and advocacy that have sought to publicize tobacco industry marketing approaches might focus on how tobacco companies use packaging to entice young consumers to their brands.

The picture that emerges may reveal, for example, a site where research and excavation are paramount while visitation and interpretation to the public is restricted or even prohibited; a site where use for social and tourist purposes is balanced with research and excavation; or a site where tourism prevails, infrastructure development is extensive, and excavation is forbidden. Whatever the picture is, there should be a demonstrable correspondence between it and the values identified in the assessment of significance; that is, the picture should reflect what is valued at the site. In writing policy statements, therefore, it is important that context is conveyed by indicating what values are being preserved or what constraints or conditions prevail that make preservation of a value difficult or impossible. Policies, therefore, set the stage for why the managing authority is following a particular trajectory for a site. What will be done and how it will be achieved are the actions that come later with the development of objectives and strategies. At this stage it is necessary to identify specific objectives related to the policies defined for each programmatic area or activity. The distinction between objectives and strategies is not always clear and even the most experienced practitioner can become confused. One way to think about the distinction is to see objectives as destinations and strategies as the road map to the destination. Mastering the distinction, however, is not nearly as important as simply setting clear targets for achieving the purpose for which the site is being managed, whether those targets are framed as objectives or strategies. One method used by practitioners to clarify objectives and to make them more targeted and measurable, is to state what will have been achieved within a specific time frame (for instance, by the end of five years we will have achieved these specific objectives), then list them. In this way the objective can be formulated more concretely, since its results are envisioned. An example of an objective related to tourism and interpretation could be to have undertaken a visitor survey (within a specified period of time) in order to better understand the types of visitors and their motivations and interests in visiting the site. Strategies are the most detailed level of planning, specifying how the objective will be achieved and establishing resources required and time frames and responsibilities to get the work done. If an objective is to undertake a visitor survey-to continue with the example used above-the strategy will state how and by whom that targeted goal will be achieved; it may be accompanied by a detailed plan, which in this case might specify the methodology to be followed, the questions to be asked, and the personnel and budget required. Unfortunately, the development of strategies for intervention is too often the stage at which we begin when responding to the challenges of conserving and managing a site, since action is equated with progress and detailed planning is perceived as time not well spent. What typically happens when strategies are allowed to became the starting point at a site is an "organic" proliferation of independent "strategy projects"; that is, projects carried out independently by different institutions, organizations, or individuals and without reference to the objectives and priorities established in the plan. The individual projects (for example, excavation, documentation, or conservation projects, or a tourism initiative) may have their own justification, but too often they fulfill the needs of the institution or individual who is carrying them out rather than the needs of the site and the managing authority. In the development of strategies, separate, detailed plans for complex undertakings are necessary. These strategy plans must begin, however, with a clear link 671 Part V archaeologicalsitemanagement to the general plan, repeating the relevant policies and objectives of the appropriate programmatic area so that there is a clear continuity of purpose. This becomes especially important if a strategy plan is being developed by an organization other than the managing authority. Having made the decision that a certain structure, for instance, requires restoration, stabilization, or protective sheltering, it may be necessary to revisit the assessment stage to establish more detail about significance, past interventions, and present condition. This process of returning to the assessment stage is inevitable for any complex site or component of a site, since the level of detail required for a major intervention is impossible to achieve when planning long-term for the whole site. The level of detail required for full development of many strategies would, in fact, only weigh the general planning process down with data not pertinent to establishing the big picture for the site. During the course of the process and after completion, the information collected and decisions reached must be documented and written down in a plan; however, there are differing opinions about what level of information should be included in the final plan. A few remarks will suffice about the "product," which espouse a minimalist approach based on wise advice from practitioners who have written and implemented many plans. The general plan- whatever it is called-should be Holistic and integrated: Examples of fragmented authority, differing visions, and multiple implementors working at cross-purposes abound at complex archaeological sites. While it is useful and frequently necessary to bring in consultants, partners, or collaborators to develop and implement aspects of the plan, there must be one lead authority that coordinates all efforts and one plan that articulates the importance of the place and the goals for its conservation and development in the future. Short, concise, and accessible: A plan that can be understood by all the stakeholders allows everyone to easily grasp the vision and overall goals and the reasoning behind decisions, which means a plan that is short, concise, and written 672 Reading 64 demas with a broad audience in mind. Background information-whether it be interviews conducted to work out significance, detailed condition surveys, or historic documentation-is vital to preserve, but can be included in reference binders. Detailed strategy plans can and often should be separate and, in fact, are frequently developed later as the plan is implemented. As mentioned earlier, these should begin with the policy statements and objectives for the relevant category to provide the link with the general plan.

Unfortunately, the analysis included lagged values of consumption as an independent variable and estimated these equations with ordinary least squares, which is known to create biased results. Keeler and colleagues205 estimated a demand function for cigarettes with the use of monthly data from 1990 to 2000. The researchers reported that tobacco companies had been reducing traditional media advertising in favor of other marketing techniques since 1980. This was a time-series study, but since Erratum: "The author consults with a law firm that represents the tobacco industry. The paper was independently prepared by the author and was not reviewed by the law firm prior to submission for publication. Lancaster and Lancaster204 reviewed 35 single-country studies of tobacco advertising and found that overall advertising had little or no effect on consumption. These results are consistent with the industry-level advertising response function about the point N (figure 7. Some of these ban studies examined only limited bans, which are not likely to have any effect. Another analysis of adolescent and young adult initiation rates showed that after a decline in the early 1980s, there was an increase in adolescent but not young adult initiation rates. Using diffusion modeling, observed rates departed significantly from expected rates coincident with the increase in tobacco industry resources devoted to promotional activities. A study published in 2006 examined the temporal relationship between health-theme magazine advertising for low-tar cigarette brands and sales of these brands. Two types of low-tar brands were considered: (1) those (14 in all) that represented a brand extension of a regular-tar brand. Advertising that carried a health theme then was computed as a proportion of all advertising for these brands and plotted together with the proportion of sales of these brands among sales for all brands. For the brand extensions, the health theme began in 1965 and increased slowly until 1975 (around 5% of all advertising for these brands), then increased markedly until 1977 (nearly 35% of all advertising of these brands). Sales for the low-tar brand extensions were low (<5% of total) until 277 Time-Series Studies of Smoking Initiation and Brand Choice Besides examination of time-series expenditure data and cigarette consumption, other investigators have studied measures of smoking initiation. Pierce and Gilpin209 examined annual age-specific rates of smoking initiation from the late 1800s through the 1970s. They note changes in these rates following the launching of novel and aggressive cigarette advertising campaigns. The early campaigns were targeted at males, and this group, but not females, showed increased initiation. I n f l u e n c e o f To b a c c o M a r k e t i n g o n S m o k i n g B e h a v i o r 1976 but increased rapidly until 1982 (23%). By 1985, the health-theme advertising had returned to a low level (just over 5%), but sales remained high, reaching 25% in 1990. Sales peaked at about 15% in 1981 and declined slightly thereafter to 10% in 1990. For both brand types, marked increases in health-theme advertising were followed by increases in sales. It appeared, however, that once the brand extensions were established, further such advertising was not necessary to retain brand share, but advertising was needed for the exclusively low-tar brands. Further information on advertising for lowtar cigarettes appears in chapters 4 and 5. Adolescents perceive that smoking will contribute to popularity and that advertising conveys this message. In addition, tobacco company documents show that marketing for cigarette brands popular with youth associates smoking those brands with popularity. Many adolescents perceive that smoking will confer attributes associated with success with the opposite sex-toughness in the case of boys and slenderness in the case of girls. Girls are more likely to smoke if they think it will help them be thin and attractive.