"Discount 100 mg viagra jelly visa, erectile dysfunction 5k".

N. Zakosh, M.A.S., M.D.

Co-Director, California Northstate University College of Medicine

It has germline-limited chromosomes (Es for "eliminated"), paternal genome loss, and monogenic broods in which the sex of offspring is determined by maternal genotype (Hatchett and Gallun 1970, Stuart and Hatchett 1988). That they should acquire fertility genes-or have such effects-is not surprising: they are only found in germinal cells and they are so much more numerous than the somatic chromosomes (28 vs. Unlike L chromosomes, E chromosomes are eliminated in spermatogenesis and have predominantly maternal inheritance (White 1973). Hybridogenesis, or Hemiclonal Reproduction In hybridogenesis, individuals from 2 species mate to form a hybrid that is fertile but only transmits the haploid genome of one parent-the other haploid genome is discarded during gametogenesis. Thus haploid genomes from the donor species can invade the recipient host species. Often the hybrids are of one sex only (female), and so the system amounts to motherdaughter transmission of an entire haploid genome with the other half borrowed anew each generation and then discarded. Thus the system is also called hemiclonal reproduction: offspring are produced that combine a usually invariant maternal genome (hemiclone) with a recombinant, sexual paternal genome. Hybridogenesis is best known from the fish Poeciliopsis, the frog Rana esculenta, and the stick insect Bacillus (Table 10. A possible case of incipient hybridogenesis is found in a midge (Polukonova and Belianina 2002). We begin with Poeciliopsis, which was the first case to be studied in some detail. The Topminnow Poeciliopsis Poeciliopsis is a genus of small freshwater fish (Box 10. Due to some unknown peculiarity of sex determination, these are all females, and so F2 progeny cannot be produced. But if these hybrid females are backcrossed to lucida males, a striking result is observed: the offspring are no more lucida-like than the F1 hybrids (reviewed in Schultz 1977). One can repeat this backcross for as many generations as one wishes, and still the monacha traits are not diluted out. The implication is that the hybrid females only pass on the monacha genome in their eggs and exclude the lucida genome, and this conclusion has been confirmed with allozyme polymorphisms-in each case, hybrids only transmit the monacha allele, not the lucida allele. This aberrant mitosis is followed by an abbreviated 1-step meiosis, in which the monacha chromatids separate into chromosomes. The frequency and diversity of monacha-occidentalis hemiclonal females is much higher where occidentalis and monacha overlap and can hybridize (Vrijenhoek 1979, Angus 1980, Quattro et al. By contrast, streams with low clonal diversity are thought to be derived from a single hybridization event. The frequency of monacha-lucida hemiclones is less variable, with hybrid females found almost everywhere that lucida is found. In principle, the driving monacha hemiclone has a 2-fold fitness advantage over occidentalis or lucida genotypes, and so it might be expected to increase in frequency and go to fixation, at which point it would drive both the host species and itself extinct. As with driving sex chromosomes, there must be some countervailing frequency-dependent selection pressure preventing it from going to fixation. In Poeciliopsis, the dominant force appears to be the strong avoidance of hybrid females by lucida or occidentalis males. Laboratory mate choice experiments show that male lucida have a great reluctance to mate with monacha-lucida females (which should not be surprising, because the hybrid is an evolutionary dead end for their genes; McKay 1971). Furthermore, this mate choice seems to produce the sort of frequency-dependent effects that would keep hemiclones at an intermediate frequency. As with other members of the Poeciliidae (including guppies, killifish, platyfish, swordtails, topminnows, and mollies), there is internal fertilization and live birth (males have an intromittent organ called a gonopodium). The genetics of sex determination are not well understood: there are no obvious sex chromosomes and within the family Poeciliidae there are species with male heterogamety, female heterogamety, and a mixture of the two. As well as diploid sexual and hemiclonal taxa, there are also triploid asexual, all-female taxa that must mate with a sexual male in order for development to begin ("gynogenesis" or "pseudogamy"). In addition, there appears to be a "rare hemiclone" advantage in attracting males, which would contribute to the maintenance of hemiclonal diversity within a single site (Keegan-Rogers 1984). And male mate choice is probably not the only factor preserving stability (and as we shall see, it apparently does not act at all in the parallel case of Rana esculenta). Ecological differences also exist between sexuals and hemiclones that could allow "niche partitioning" (Weeks et al.

He concluded by saying that Hamet had a great span of networks that facilitated his ability to obtain funds. His application indicated that he would spend 25 percent of his time working on this project (Hamet, 1990). She was also responsible for initial plating, cell maintenance, cell determinations, thymidine incorporation and cytofluorometry. Steve Pang, a postdoctoral researcher and co-author on many of the publications, worked in the laboratory for about two years. Vratislav Hadrava, who also came from the Czech Republic, had just finished his medical degree and was looking to start a PhD. His previous laboratory experience involved work on the basic mechanisms of cell growth. Pressure overload induces cardiac growth in the rat, which implies hypertrophy of cardiac muscle cells and proliferation of non-muscle cells. The team confirmed that an increase in pressure induced apoptosis, mainly in the cardiomyocytes. Cardiac hypertrophy was thus thought to offer a new target for therapeutic intervention. Nine publications were excluded from the bibliometric analysis as they presented preliminary findings and were published prior to the case study grant. Of the 18 included articles, only 16 were included in the citation analysis because two were not indexed in the Web of Science. The team also disseminated findings through students, networks and conferences such as the annual meeting of the International Society on Hypertension, at which Hamet was a keynote speaker. Members of the research team said that Hamet encouraged them to send in abstracts with preliminary results, as well as final papers. Hadrava mentioned that these publications and presentations were important in Of the nine publications that were indirectly linked to this grant, all were indexed in Web of Science, receiving 182 citations in total and giving a relative citation impact of 0. Hamet also explained that the team disseminated findings to health practitioners and those involved in health management at the provincial and federal level. The bibliometric analysis also investigated knowledge diffusion, which found that Hamet and his team most commonly publish in the areas of vascular disease. Their work is most commonly cited by those working in vascular disease, cardiovascular surgery and cardiovascular systems and by those from the United States and Japan. Hamet has authored and co-authored more than 450 scientific publications and holds several international patents. Of these patents, Hamet claims some are partially related to the case study grant. Active in many societies, Hamet is President-Elect of the International Society of Pathophysiology. He was also President of the Canadian Hypertension Society and General-Secretary of the International Society of Hypertension. He has received many prizes, including the Distinguished Scientist Award of the Canadian Society for Clinical Investigation and the Achievement Award of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society in 1996. In 2001, he received the prestigious Wilder-Penfield award from the Quebec government. In addition, he received the Canadian Hypertension Society/Novartis Distinguished Service Award. Dr Hadrava came to Canada in 1985 after obtaining a medical degree in the Czech Republic. Hadrava claimed that his involvement in this project was at the beginning of his professional life. He said that his work on growth factors and receptors and how they relate to the cell cycle was applicable to his post-doctoral fellowship, in which he was studying neural transmitters and how they relate to receptors and influence neuronal activity. After his post-doctoral appointment, Hadrava completed the Canadian medical examination with the expectation that he would apply for a residency.

Lipid A has been shown to be the toxic factor in Gram-negative sepsis and can activate the classical complement pathway. Bacterial Invasion Listgarten (1965) described the superficial (250 urn) penetration of spirochetes in the ulcerated region of acute necrotizing ulcerative lesions. Spirochetes were found in the non-necrotic tissue before other bacteria and present in higher concentrations within the intercellular spaces of the epithelium adjacent to the ulcerated lesion, as well as within the connective tissue. Frank and Voegel (1978) and Frank (1980) have reported the presence of filaments, rods, and coccoid organisms in the intercellular spaces of human pocket epithelium. In one case the bacteria had traversed the basement lamina and reached the connective tissue. Gillett and Johnson (1982) observed the bacterial invasion of the connective tissue in cases of juvenile periodontitis, using electron microscopy. The invading flora was described as mixed but composed mainly of Gram-negative bacteria, including cocci, rods, filaments, and spirochetes. Nisengard and Bascones (1987) published informational overviews from a workshop on bacterial invasion in periodontal disease. The number of Gram-negative bacteria in connective tissue was significantly higher in sites with ongoing attachment loss than at inactive sites. The authors indicate that bacterial invasion, in which proliferating bacteria penetrate the tissues, should be differentiated from bacterial translocation, in which bacteria are passively transported into the tissues by mechanical means such as biopsy or histological processing. The presence of coated pits in the epithelial cell surfaces suggested that internalization of Pg was associated with receptor-mediated endocytosis. Conceptual problems include the complexity of the microbiota, with approximately 300 bacterial species present in plaque. If combinations of species are involved in active disease, the complexity increases dramatically. Another difficulty is the inability to accurately define the disease status at a given site at the time of sample collection. Current methods of disease detection only allow for detection of sites which have recently lost attachment over a period of time. Technical difficulties are present at the time of collection of the bacterial sample, cultivation, and characterization of the bacteria. The small diameter of the sulcus and the lack of a "gold standard" makes it impossible to determine if a representative sample has been collected. The dispersion process following collection of the sample tends to create error by selecting more robust microbes which survive the dispersion process. In the culture process, it is impossible to determine if all bacteria originally sampled grow out. Furthermore, cultured bacteria cannot always be characterized and identified, leading to further error. In an in vitro study of bacterial sampling by absorbent paper points, Baker et al. From a practical standpoint, it is likely that few of the bacteria from the apical portion of the pocket are detected, leading to error in the bacteriologic assay. Indigenous organisms are constant members of the microbiota while exogenous organisms are transient. Opportunistic organisms overgrow as a result of environmental changes or alteration of the host resistance. Technical advances in anaerobic culturing have allowed the identification of specific bacteria associated with health and periodontal disease. Healthy sites harbored a sparse plaque, mostly Gram-positive cocci like Actinomyces and Streptococci. It must be remembered that if the causative agents are indigenous, they will be difficult to eradicate. They found that gingivitis began in 10 to 21 days and resolved within 1 week of renewed oral hygiene efforts. During phase 2 (days 2 to 4), filamentous forms and rods increased, although cocci were still present in large numbers. Phase 3 (days 6 to 10) was associated with a gradual shift to vibrios and spirochetes. When the oral hygiene was resumed and healthy gingival conditions re-established, the gingival flora returned to one of predominantly Gram-positive cocci and short rods.

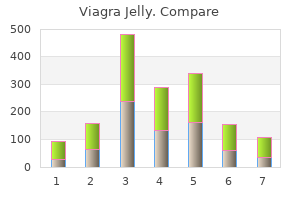

Structure and Content Size Jones (1995) has recently reviewed evidence on the size distribution of Bs in plants. In no plant species is the B chromosome larger than the largest A and in only a few species is the B roughly the size of the largest As. In fully 40% of the species, the B is one-fourth to three-fourths the size of the average A. In 26% of cases, the B is smaller than the smallest A (but not tiny) and in 30% it is a tiny microchromosome. In short, Bs are generally small and in more than one-half of all cases are smaller than the smallest A. The smallest in any plant species is found in the fern Ophioglossum (Goswami and Khandelwal 1980); and in animals, the smallest B is in 2 species of the fly Megaselia, in which the B is little more than a centromere (Wolf et al. Unfortunately, there is no phylogenetic evidence that would allow us to order the size of Bs. Are Bs initially larger and selected to become smaller as genes are shut down that are redundant on the As (Green 1990) Or do Bs often start very tiny and sometimes grow in size, as when they add repeated sequences useful in drive In animals, the B is sometimes as large as the largest A and, in one case, larger: the cyprinid fish Alburnus alburnus has a B that is infested 360 B Chromosomes Figure 9. Percentage of plant species that have Bs for 4 categories of B size: tiny, dot-chromosomes (micro); larger than micro but smaller than smallest A; somewhat smaller than the average size of As (one-third to three-fourths of A size); larger than the average size of the As. As pointed out by Hewitt (1979) and reaffirmed since then (Camacho 2005), large Bs are more likely to be mitotically stable, while small ones may be unstable and, thus, vary in number within an individual. This variation, when it occurs in germinal tissue, may make drive more likely, while in somatic tissue it could make B elimination from selected tissues, for example, root cells, more likely. Many show only 2 forms, such as the large and the microsized one in Brachycome dichromosomatica (Smith-White and Carter 1970). The origin of many of these polymorphisms can be explained by reference to centromeric misdivision, in which a single B at meiosis may give rise to 2 unequally sized acrocentrics, and then their isochromosomes, and then further derivates by deletions. Chives (Allium schoenoprasum) provides an example of the opposite, namely high structural polymorphism of Bs. In Wales 7 different forms combine to give as many as 29 different B karyotypes (Bougourd and Parker 1979a, 1979b). Polymorphism may also result when drive at female meiosis is strong for univalents, but weak or absent in 2B individuals due to meiotic pairing. Then as 1 B form increases in frequency, thereby increasing the number of 2B individuals, new mutants are favored that do not pair with the old B but instead continue to act as univalents, with drive. This is a form of frequency-dependent selection, with rare variants favored because they will rarely pair with themselves, and common ones disfavored for the opposite reason. Heterochromatin Bs are often assumed to be mostly heterochromatic, but this is truer of animals than plants. In plants, Bs may often be euchromatic or contain major euchromatic segments, apparently about as often as A chromosomes. There is even one species, Scilla vedenskyi, in which all 5 autosomes show heterochromatin but the B does not (Greihuber and Speta 1976). C-banding is supposed to reveal constitutive heterochromatin but "in terms of structure and organization of Bs in plants there seems to be no specific useful information to be had so far from C-banding studies" (Jones 1995). In such an intensively studied species as maize, the complete absence of B genes with a growing list of A genes was clear more than 20 years ago (Jones and Rees 1982). The other host characters are leaf-striping (in maize), male fertility, achene color, crown rust resistance, and a regulatory effect on an A esterase gene, but for some of these 362 B Chromosomes the evidence is weak. And inactive ribosomal cistrons are spread throughout the B of Rattus rattus (Stitou et al. We believe this may be because Bs often evolve from the centromeres outward, beginning with very few genes and having such genes rapidly invaded by centromeric and pericentromeric repeats, which give an advantage in drive. The characterization of these repeats has, in turn, given us our first unambiguous evidence regarding genetic homology to sequences elsewhere in the genome. At the same time, Bs that are euchromatic may harbor large blocks of tandem repeats, as in the Australian daisy Brachycome dichromosomatica (Leach et al. Because the genomic organization of the B is nothing like that of any of the As, it could not have originated by simple excision, nor did it contribute to the polymorphic heterochromatic segments also found in the species (Houben et al.