"Cheap desloratadine 5mg visa, allergy shots three times a week".

N. Khabir, M.B.A., M.D.

Program Director, Rush Medical College

Identify all illnesses or conditions which you know have occured in you or your blood relatives. Sisters Sons GrandDaughters parents None (Signature of Person Completing Form) (Relationship to Patient) (Date) (Signature of Provider) (Reviewed/Dated) Signature of Provider Signature of Provider Signature of Provider Signature of Provider Signature of Provider Signature of Provider Reviewed/Updated Reviewed/Updated Reviewed/Updated Reviewed/Updated Reviewed/Updated Reviewed/Updated Page 4 of 4. The vestibular bulbs cause ``vaginal' orgasmic contractions, through the rhythmic contraction of the bulbocavernosus muscles. Because of the engorgement with blood during sexual arousal, the labia minora become turgid, doubling or tripling in thickness. The corpus spongiosum of the female urethra becomes congested during sexual arousal; therefore, male erection equals erection of the female erectile organs. The correct anatomical term to describe the erectile tissues responsible for female orgasm is the female penis. Orgasm is an intense sensation of pleasure achieved by stimulation of erogenous zones. Women do not have a refractory period after each orgasm and can, therefore, experience multiple orgasms. Sexologists should define having sex/love making when orgasm occurs for both partners with or without vaginal intercourse. For years, it has been assumed that the female orgasm is due to the female erectile organs (Masters and Johnson, 1966; Hite, 1981; Laqueur, 1992; Puppo et al. In the last few decades, in sexology and in sexual medicine (Goldstein, 2000; Goldstein et al. The anatomy of the female erectile organs is described in human anatomy textbooks (Testut and Latarjet, 1972; Chiarugi and Bucciante, 1975; Standring, 2008; Netter, 2010; Puppo, 2011a), but in sexology textbooks (Komisaruk et al. The female perineum (from Puppo, development of the internal and external genital organs in males and females. It is important to know this because it is related to the function of these organs, that is, the internal genitals have a reproductive function while the external ones have the function of giving pleasure' (Puppo, 2011a). The labia majora are two prominent cutaneous folds and from the mons pubis, reach up to the perineum, and correspond to the male scrotum; normally they are in contact and separated only by the vulvar cleft (rima pudendi). When the labia majora are separated, two smaller folds are seen, the labia minora, which anteriorly embrace the clitoris, and in the space between them. The mucosa of the vaginal vestibule, which originates from the embryonic endoderm, is nonkeratinized (Farage and Maibach, 2006). The human sexual response can be physiologically described as a cycle with four phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution. A: Clitoris, corpora cavernosa and glans; B: penis, corpora cavernosa and corpus spongiosum (glans, pars intermedia, and bulb). This review aims to clarify some important aspects of the anatomy and physiology of the female erectile organs and of the female orgasm, which are necessary for correct. The clitoris is an external organ and has three erectile tissue parts, most of which lie beneath the skin: the glans, the body, and the crura. The clitoris, in the free part of the organ, is composed of the body and the glans located inside of the prepuce, which is formed by the labia minora (Testut and Latarjet, 1972; Chiarugi and Bucciante, 1975; Standring, 2008; Netter, 2010; Puppo, 2011a). The diameter of the glans ranges from the 3 to 8 mm, and the most common diameter is 45 mm. Parity influences clitoral size but age, height, weight, and oral contraceptive use do not (Verkauf et al. Studies by Dickinson (1949) found that clitoral size ``is not necessarily a criterion of responsiveness. A very tiny clitoris, so thin and low it can hardly be picked up by the fingers, may be associated with powerful orgasm from friction or pressure on the organ alone' ``the other relevant finding is the extent of excursion, or the range of mobility of the glans'. The clitoris is attached by the suspensory ligament to the front of the symphysis pubis (Dickinson, 1949; Testut and Latarjet, 1972); the suspensory ligament is a structure with superficial and deep components (Chiarugi and Bucciante, 1975; Rees et al. If the genital tubercles are hypoplastic or fail to fuse, the clitoris may be extremely small or absent (Neill and Lewis, 2009). The dimensions of the clitoris vary; ``clitoromegaly is defined as a clitoral area greater than 3545 mm2' (Oyama et al. Acquired clitoral enlargement is relatively rare in adult females and occurs under a variety of circumstances, ``the causes of clitoromegaly can be classified into four groups: hormonal conditions, nonhormonal condi-. Pseudohypertrophy of the clitoris has been reported in small girls due to masturbation with the chronic manipulation of the skin of the prepuce leading to mechanical trauma, which expands the prepuce and labia minora resulting in clitoral enlargement (Copcu et al.

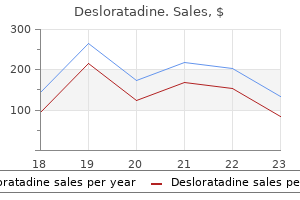

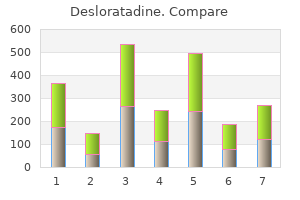

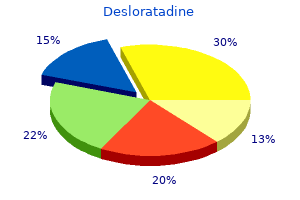

With the intent of providing consistent and reproducible dosimetric information without increasing healthcare costs the following guidelines are suggested. The standard deviation with training is smaller indicating that training can reduce variability in prostate contouring between individuals. Volume of the rectum receiving greater than 100% of the prescription dose should be recorded. A Foley catheter should be used during day 0 imaging, and the urethra should be contoured on all slices within the prostate. The magnitude of this effect further depends upon the timing of imaging after the implant for the purpose of dose evaluation and dose reporting. At least 15 and sometimes more than 30 guiding needles or needle-insertions are needed to place the sources to various spatial locations in the gland. The mechanical trauma caused by the needle insertion, the intraprostatic bleeding resulting from the needle penetrations, and the general inflammatory response to the needle perforations together cause the prostate gland to swell initially and reach a maximum volume shortly after the completion of procedure followed by gradual resolution of the swelling. Schematic illustration of the time course of prostate volume following source implantation. Prostate edema is typically characterized by an edema magnitude and a resolution halflife. The characterization of edema resolution for t > Tmax requires explicit knowledge on the functional form of the resolution. In a comprehensive study, it was demonstrated that the edema resolution could be described by a single exponential decaying function. When edema resolution deviates from the exponential decay function one may need 2nd or 3rd resolution half-lives for a more comprehensive characterization. Table 4 summarizes the edema magnitude and the 1st resolution half-life reported by various studies. Edema Magnitude It should be noted at the outset that the edema magnitudes reported in the literature were not always determined under the ideal condition for Eq. When a selected time for imaging study deviates from the true Tmax, the edema magnitude would be underestimated by an amount that is dependent on the timing (see. When different imaging modalities are used for volume measurements, additional uncertainties are introduced because the amount of tissue visualized by different imaging modalities can be systematically different. The imaging time associated with various reported edema magnitudes ranged from immediately after the insertion of all guiding needles to immediately or several hours after the completion of source implantation to approximately 1 day or 3 days after the procedure. It also introduced additional artificial variations to the reported edema magnitudes that, if not fully appreciated, could lead to underestimation of the true magnitude of edema. Continued volume increase from implant-day to 1 week post-implant (by about 5%) had been observed in some patients. The average residual edema magnitude at 30 days post-implant can be on the order of 10%. The 1st Half-life of Edema Resolution There were only a few studies that can adequately address the quantitative edema resolution characteristics. They reported that the edema resolution fitted nicely to an exponentially decaying function for all 10 patients included in the study. The edema resolution half-life determined from the fit ranged from 4 to 25 days with an average of 9. Eight of the ten patients demonstrated edema with a half-life of less than 10 days. Neither the magnitude nor the halflife was found to correlate with the number of needles used, radionuclide used, the number of sources implanted, and the total source strength. The resolution is relatively quick for the first 2 weeks followed by a slow resolution that can last more than 1 month. Theoretical Expectations the procedure-induced prostate edema and its dynamic resolution force the treatment volume and the implanted source locations to vary with time. Conventional pre- and post-implant dosimetry, however, are based on static prostate volume and source locations determined at, typically, one user-selected time which does not take into account the dynamic variations caused by edema in the calculation of dosimetry indices. The influence of prostate edema on conventional implant dosimetry has been recognized and studied by many research groups since the late 1990s. The conventional post-implant dosimetry could either underestimate or overestimate the delivered dose depending on the timing of post-implant imaging study. If the prostate volume and source locations are measured shortly after the completion of the procedure (when the edema is large), the post-implant dosimetry is expected to underestimate the delivered dose.

Semantic Memory and the Medial Temporal Lobe Memory System Studies of patients with amnesia due to damage to the medial temporal lobes have established three broadly agreed on facts about the functional neuroanatomy of semantic memory. Damage to these structures results in deficient acquisition of new facts and public events and the extent of this deficit is roughly equivalent to the deficit for acquiring personal information about day-to-day occurrences. However, despite broad agreement that acquiring semantic memories requires medial temporal lobe structures, there is disagreement concerning the role of the hippocampal region. One position, championed by Larry Squire and colleagues, holds that the hippocampus is necessary for acquiring semantic information. In contrast, others have argued that acquisition of semantic memories can be accomplished by the surrounding neocortical structures alone; participation of the hippocampus is not necessary. Recent studies have favored the hippocampal position by showing that carefully selected patients with damage limited to the hippocampus are impaired in learning semantic information, and that the impairment is equivalent to their episodic memory deficit. One potentially important caveat to this claim comes from studies of individuals who have sustained damage to the hippocampus at birth or during early childhood. These cases of Memory, Semantic 335 developmental amnesia have disproportionately better semantic than episodic memories, suggesting that the hippocampal region may not be necessary for acquiring semantic information. Reconciliation of this issue will depend on direct comparison of adult onset and developmental amnesias with regard to extent of medial temporal lobe damage and its behavioral consequences. The second major finding established by studies of amnesic patients is that the medial temporal lobe structures have a time-limited role in the retrieval of semantic memories. Retrieval of information about public events shows a temporally graded pattern with increasing accuracy for events further in time from the onset of the amnesia. Conceptual information about the meaning of objects and words acquired many years prior to the amnesia onset remains intact as assessed by both explicit and implicit tasks. In amnesic patients, impairments in semantic memory for information acquired prior to amnesia onset are directly related to the extent of damage to cortex outside the medial temporal lobes. Cortical Lesions and the Breakdown of Semantic Memory Studies of semantic memory in amnesia have concentrated largely on measures of public event knowledge. The reason for this is that these tasks allow memory performance to be assessed for events known to have occurred either prior to , or after, amnesia onset. These measures also allow performance to be evaluated for events that occurred at different times prior to amnesia onset to determine if the memory impairment shows a temporal gradient a critical issue for evaluating theories of memory consolidation. Because these patients have either no or, more commonly, limited damage to regions outside the medial temporal lobes, they are not informative about how semantic information is organized in the cerebral cortex. To address this issue, investigators have turned to patients with relatively focal lesions compromising different cortical areas. In contrast to the studies of amnesic patients, these studies have focused predominantly on measures designed to probe knowledge of object concepts. Concepts are central to all aspects of cognition; they are the glue that holds cognition together. It is also the level at which subordinate category members share the most properties. Studies of patients with cortical damage have documented the neurobiological reality of this hierarchical scheme and the central role of the basic level for representing objects in the human brain. Semantic Dementia and the General Disorders of Semantic Memory Several neurological conditions can result in a relatively global or general disorder of conceptual knowledge. These disorders are considered general in the sense that they cut across multiple category boundaries; they are not category specific. The defining characteristics of this disorder, initially described by Elizabeth Warrington and colleagues in the mid-1970s, are deficits on measures designed to probe knowledge of objects and their associated properties. The impairment is not limited to stimuli presented in a single modality, like vision, but rather extends to all tasks probing object knowledge regardless of stimulus presentation modality (visual, auditory, tactile) or format (words, pictures). The semantic deficit is hierarchical in the sense that broad levels of knowledge are often preserved, while specific information is impaired. Thus, these patients can sort objects into superordinate categories, having, for example, no difficulty indicating which are animals, which are tools, which are foods, and the like.

Your pathology report includes the results of tests that describe details about your cancer. When I was first faced with this decision, I was so confused I wanted to put myself in the hands of an expert. Seeking other opinions means talking about prostate cancer treatment with other doctors. You may want to talk with other prostate cancer specialists, such as those listed at the bottom of this page. Getting 2nd and 3rd opinions can be confusing because you may get different advice. Because of this, many men find it helpful to see a medical oncologist for a general view of prostate cancer treatment choices. Talking with other doctors can give you ideas to think about or help you feel better about the choice you are making. Many cancer centers allow men to meet with a urologist, radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, and pathologist in one visit. Types of Doctors Here is a list of types of doctors who treat prostate cancer: n Medical oncologist. A doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating cancer using chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and biological therapy. He or she can also treat side effects and may coordinate treatment given by other specialists. Doing so can help you feel more in control and at ease with the treatment you choose. You can learn more by reading books and articles, searching the internet, or calling organizations that focus on prostate cancer. But keep in mind that too much information can be overwhelming as you are adjusting to your diagnosis. Let your doctor or nurse know what else you need to know to be comfortable reaching a decision. Some men want to read books and articles about the current research on prostate cancer treatment choices. Others prefer to meet with men in support groups who have had prostate cancer to learn how they made their treatment choices. All of these approaches are natural ways to cope with a diagnosis of prostate cancer. To learn more about finding information on the internet see the fact sheet "How to Evaluate Health Information on the Internet" at. Your spouse or partner will also feel a range of feelings, but not have the same ones at the same time as you do. Finding out you have cancer can bring up fears of the cancer getting worse or of dying. You may also worry about changes to your body or being intimate with your spouse or partner. Many men describe a feeling of loss-loss of the life they had before cancer, loss of energy levels, or the physical loss of the prostate. If you find that you need time to adjust and sort out your feelings and values, let your spouse or partner and family know your needs. Chances are that they are also trying to cope with the news and may not know how best to help you. If you are holding your worries and feelings inside for too long and your silence is hurting you or your family, ask your doctor, counselor, or religious leader for suggestions about getting help. Reaching a decision about how you want to treat your prostate cancer is very personal-it is a balance of what is important to you, what you value the most, what types of treatment choices are available to you, and what the benefits and risks are. Talking With Others Along with talking with their doctors and spouse or partner, many men find it helpful to talk with others, such as: n Family. There is a lot to learn from other men who have faced these same prostate cancer treatment decisions.

In contrast, the dividing septum of a monochorionic placenta consists of two thin amnions. One placenta, same-sex fetuses, and absence of a dividing septum suggest monoamniotic twins, but absence of a dividing septum may also be due to septal disruption. Pathologic examination of the placenta(s) at birth is important in establishing and verifying chorionicity. Zygosity determines the degree of risk of chromosomal abnormalities in each fetus of a multiple gestation. Second-trimester maternal serum screening for women with multiples is limited because each fetus contributes variable levels of these serum markers. First-trimester ultrasonography to assess for nuchal translucency is a more sensitive and specific test to screen for chromosomal abnormalities. A secondtrimester ultrasonography exam is important in surveying each fetus for anatomic defects. Gestational diabetes has been shown in some studies to be more common in twin pregnancies. Spontaneous abortion occurs in 8% to 36% of multiple pregnancies with reduction to a singleton pregnancy by the end of the first trimester ("vanishing twin"). Possible causes include abnormal implantation, early cardiovascular developmental defects, and chromosomal abnormalities. Before fetal viability, the management of the surviving co-twin in a dichorionic pregnancy includes expectant management until term or close to term, in addition to close surveillance for preterm labor, fetal well-being, and fetal growth. The management of a single fetal demise in a monochorionic twin pregnancy is more complicated. The surviving co-twin is at high risk for ischemic multiorgan and neurologic injury that is thought to be secondary to hypotension or thromboembolic events. Termination of pregnancy may be offered as an option when single fetal demise occurs in a previable monochorionic twin pregnancy. In a large retrospective cohort study, the incidence of placental abruption was 6. Preterm premature rupture of membranes complicates 7% to 10% of twin pregnancies compared with 2% to 4% of singleton pregnancies. Preterm labor and birth occur in approximately 57% of twin pregnancies and in 76% to 90% of higher order multiple gestations. Approximately 66% of patients with twins and 91% of patients with triplets have cesarean delivery. Breech position of one or more fetuses, cord prolapse, and placental abruption are factors that account for the increased frequency of cesarean deliveries for multiple gestations. The average duration of gestation is shorter in multifetal pregnancies and further shortens as the number of fetuses increases. The mean gestational age at birth is 36, 33, and 29 and one-half weeks, respectively, for twins, triplets, and quadruplets. The likelihood of a birth weight 1,500 g is 8 and 33 times greater in twins and triplets or higher order multiples, respectively, compared with singletons. In two multicenter surveys, multiples occurred in 21% to 24% of births 1,500 g and in 30% of births 1,000 g. The mechanisms are likely uterine crowding, limitation of placental perfusion, anomalous umbilical cord insertion, infection, fetal anomalies, maternal complications. The smaller twin has an increased risk of fetal demise, perinatal death, and preterm birth. Five percent to 15% of twins and 30% of triplets have fetal growth discordance that is associated with a sixfold increase in perinatal morbidity and mortality. The death of one twin, which occurs in 9% of multiple pregnancies, is less common in the second and third trimesters. In this case, the co-twin is either completely resorbed if death occurs in the first trimester or is compressed between the amniotic sac of its co-twin and the uterine wall (fetus papyraceous). Other complications involving the surviving co-twin include antepartum stillbirth, preterm birth, placental abruption, and chorioamnionitis.